My name is Nnamdi Onwualu. I was born in 1952…1952. December 1952.

I was born in the northern part of Nigeria in a town they call Bakori. It’s in Katsina state now. My early years were spent in the North until I left, well as a child still, I came back to go to school in the East and then I didn’t go back to the North again until after the war.

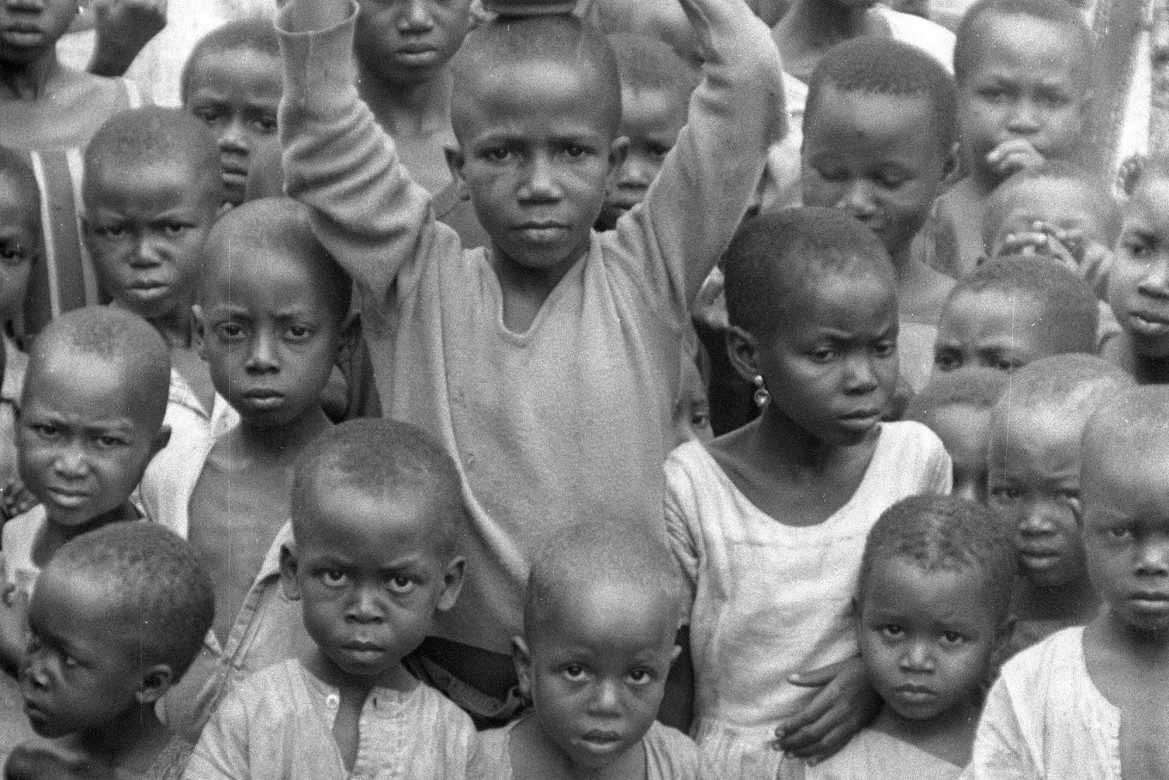

Nnamdi Onwualu remembers the 1967-1970 Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

My mother, well that’s my grandmother, my grandmother was a business woman. She dealt in, well she sold wares and sometimes also they got drinks from Cameroon. Hot drinks which weren’t generally accepted by the Northerners because of their religion. They don’t drink it. That is officially speaking. But of course, they were the major customers. My father was in the East. He was in the North before but then he later went down to the East but my mother was with my grandmother. They were doing the business together.

I went into the war a boy and came out a man

[When I think about the Nigerian-Biafran War] what comes to my mind is a lot of things, a lot of things actually. The disturbances of 1967. The killings in the North that precipitated the war. It was a very traumatic time. I lost my father and my grandfather during the war. I lost many friends also during the war.

The greatest effect of the war on me was that I became a man before I was a boy. Everything was truncated. I went into the war a boy and came out a man with experience far beyond my years. In a way, it also prepared me for the future life. Despite everything that happened, I owe my war experiences for a lot of the decisions. The ability that I had to cope through after the war and put things together, helped my mother to hold the family together, to complete their education and come back to regular life.

I was following everything. I was listening to the broadcast of Colonel Ojukwu. I was listening to the announcement, to the broadcast from the beginning until the Biafra was declared. And of course, we erupted in joy all over the place. The wave of killings in the North had happened for so long and there was no response from the Nigerian government. Everybody who had anybody who was living in the North was agitated.

The wave of killings in the North had happened for so long

Many didn’t come back and we heard and we saw live accounts of those who were there- how they were butchered, what happened to our people that were living in the North. And there was nothing coming from the Nigerian government so we all followed on a day to day basis development in Nigeria up to that point. It didn’t come as a surprise. The people were agitating. Many actually thought it should have been declared a long time before that May 27 or is it 31st? Yes. Before.

I was in secondary school. I was in class three. That should make me I think about 15.

The schools were closed and eh, already we had started training. Every young man has started their training. We called it civil defence. Civil defence, yes. We were training with wooden guns not knowing what would really come.

I come from Onitsha. Onitsha is on the banks of River Niger. The bank of river Niger that separated the Igbo heartland from the Nigerian heartland or south of Nigeria. We were the people that were receiving the Igbos that were being killed all over Nigeria. Because of the influx of these refugees, there was no place to place them so schools started closing because they were needed for refugee camps. They had to be settled somewhere so school had to be suspended. Well, initially when we left school, we thought well within a short time we’d go back but things didn’t happen that way.

More and more people were still coming in. Matters were getting worse. There wasn’t anything to feed them with.

Some died inside the trains that brought them

Everybody, young and old, we threw ourselves collectively into providing for the refugees coming back from different parts of Nigeria. Well, Eastern Nigeria was still part of Nigeria then so we were making provision for them.

But as the killing continued, it seemed like this thing wouldn’t stop anytime soon.

I don’t know how many soldiers were from the East but a lot of them were killed in different places in Nigeria. There was a general movement for all the young men now gathered and then some of the people who had already retired started training the young men, at least for them to know what they need to do in case there’s war. And even women, even old women were being trained how to take cover. Nobody ever heard the thing about these things. It was exciting for us young people anyway in the deadly thing.

They [refugees] came back with nothing. They were haggard. Most of them came without any property. Many of them were wounded. Some died inside the trains that brought them. Those who were not lucky enough even to get on the train, they walked through the bushes and hid. Hiding in the day, walking in the night until they got back to Eastern Nigeria.

…the level of hate…was unbelievable

The refugees were coming into Enugu by the train. Onitsha had no train but then sometimes they would get through from Asaba and cross over to Onitsha. We saw them. Those who came through that way, we saw them in Onitsha.

Some schools in Onitsha, many schools in Onitsha were used also for refugee camps. There was a school very near my home. Originally some refugees were camped there then later they were moved out more into the entire hinterland and then a military outfit was now posted there.

[Seeing those refugees], I felt like just going into Nigerian army and slaughtering everybody. That was the level of the anger because it didn’t really matter what you did, whether you were a soldier or not, whether you were a child or, we heard unbelievable stories. Pregnant women were cut open. Their babies dashed or killed there also, to make, the level of hate that followed the killings was unbelievable. Like everybody else, I was angry. I was particularly angry. I felt like they should just give me a gun now.

we didn’t wait to be recruited

Well, like I said I was about 15 then. I volunteered [to join the Biafran Army] but was rejected. They said we were too young but we were burning with zeal. However, some of my classmates who were taller, I wasn’t that tall, looked more adult. They easily got recruited. I was disadvantaged. My height was a disadvantage but the bigger boys, they got recruited.

At that initial time when we went to join, we were turned down but then by 1968 a lot had happened. A lot of people had been killed also, including soldiers. So many of them who joined early had already been killed.

It was in that war front that I saw my father’s dead body

By the time Nigerian troops invaded Onitsha in 1968, this was my hometown, and at that point we had already had civil defence training, volunteered to fight but were turned down. But then when it came to Onitsha, we didn’t wait to be recruited.

We formed a body of volunteers and went and engaged.

That was where I started fighting.

It was in that war front that I saw my father’s dead body otherwise nobody would have known what happened to my father. He was a water engineer so usually when there’s fault in the water system, there’s a large tank inside the Onitsha main market. From time to time it does happen, they would gather their crew and go for maintenance so probably the early assault knocked out the water system and probably they alerted [him] to come to them [because] there was no water in their place so they gathered their people and went down because where I saw his body was among some other civilian bodies.

Probably this must be the gang that went down to do the water repairs. It was towards the bank of the river and that was the first place occupied by the Nigerian troops when they landed. Probably. I wasn’t there to say categorically but then that was where he fell.

When I checked his body I could see a bullet hole in his head and some of the other bodies there, all of them had bullet wounds. They were already dead.

[Whistles]

From the distance where we were initially and after pushing federal troops down one Ajasa Street, we went down there then we got to one mango tree that was in front of the small market there. Then, there concentration was too much so the seasoned soldiers who were with us asked if anybody knew how we can circumvent. I went to school in that part of town. I knew the place like the back of my hand. Me and few of the volunteers who were familiar with the place took them round to go another way to go through– there’s a Roman Catholic maternity hospital.

…anger rose in me…

We wanted to get through there to strike out to the smaller market. It was at that point we looked. We saw some dead bodies. Something familiar but of course a body lying down you can’t really know. Something familiar with the, I don’t really know what it was until when we were crossing I crossed passed my father, then first I recognized the long clothe that he was tying. His normal habit in the morning especially when they go for this kind of emergency. They would just tie up a long clothe with a shirt.

It was the clothes that was familiar and now there was his face, face to face with me.

I froze.

I didn’t fear anything.

In fact, there was an older soldier, Sergeant World Class. He pulled me in. I didn’t really know what happened but he pulled me in and said, “Are you crazy? Why are you?”

So I couldn’t’ even talk. I tried to talk but it was blocked. I couldn’t say anything.

But, well, the fighting was still going on so we continued but from that point, the anger rose in me so even at the point when some of the older soldiers came and they were saying, “Yes, you people have done well to help our soldiers” I said I wasn’t moving anywhere. I would see this operation to the end and I did.

And I did.

You know the thing with, well I don’t know whether modern warfare is like that, sometimes you know the general direction of where your opponents are. You open fire in that side.

Nobody can say who killed who. Nobody can say who killed who.

I went out with my father’s double barrel gun

The only two occasions I remember clearly was a surprise meeting of some federal troops in a veranda where we thought we had already cleared only to find somebody at the back there. He was surprised to see me. I was surprised to see him. He’s a trained soldier. He opened fire first but luckily he missed. And even as he was still changing his magazine to– I was still standing petrified and then there was something just like, “shoot me then.”

I returned fire and he fell.

I didn’t wait to see whether he died or didn’t die.

I just jumped back into the gutter and ran back.

Then, the second time was by the time we had already now pushed back, the boats that brought them were stuck. One was stuck in the sand bank in the middle so they had nothing anymore. Some of the canoes– because some people, Igbelegus [sic] were living on the banks of the Niger before the war. Igbelegus, yes, they’re from, they’re a tribe, I think Nupe and Igbelegus, some of them they lived on boats in Onitsha. Some of them were now hiding in those boats. I met one soldier there also, which maybe I can say, yes, at least those two. But otherwise, generally speaking, you don’t really know who killed who unless you have such close encounters.

[The Biafran fighters, we were at a disadvantage]. We should be. I was a class three secondary school student-turned-soldier overnight. These are professional soldiers. I mean, we should be at a disadvantage, I suppose. I didn’t to be honest, it was the soldier that I killed in the boat. It was his belt. That was how I got the military belt and boots. Yes. We were at a disadvantage.

I went in with my Boy Scout uniform. Then, I got boots there and the belt. Many times it was the arms we got in such operations. When I moved in, the other volunteers from my area, all of us came out with our father’s guns. I went out with my father’s double barrel gun. That was the level of anger.

It was now after we engaged in operations that I was able to recover and get a proper military rifle.

I fought to defend my town. I wasn’t a regular soldier. But then I kept up now friendship with soldiers especially those I met there. Over the period—well, it got to a point in Biafra also where even people of my age were now being conscripted and then we started running away from the conscripters because things have changed a lot by then.

Towards the end of the war, Biafra was short of trained soldiers and men so their soldiers would go on a recruitment drive. Well, actually it was conscription. It was conscription because our seniors in school, and many of them were already killed or wounded, now they had to go lower and lower in the age to bring new soldiers. Yes.

…the power of our local deity…

Yeah, I was running away this time. My father was already dead. My grandfather was dead. My mother– I was the oldest boy. If I go to them, then the family would probably have disintegrated totally. It was me that was working and feeding them during the war.

Because we were refugees.

Onitsha had been disturbed.

We had ran away. If I joined the army, then they would die of hunger. I couldn’t afford to so I had to survive. I had to stay for them to survive. Yes.

After Nigeria [Nigerian army attacked Onitsha], in 1968, that attack did not succeed. We repelled their attack. That is the entire troop that came. I think it was a brigade. Brigadier Abraham somebody. I forgot. Oluwole. Brigadier Abraham Oluwole, I remember him very well. Yes. That expedition we really de-liquidated them. After that, they didn’t come to come through Onitsha again. They had to go round and fought their way right from Nsukka through Enugu then down to Onitsha from Awka. At that point now, we ran away from Onitsha. They took Onitsha from the North. They didn’t take it from across the river.

Many people from Onitsha believed it was because of the power of our local deity that guarded the river. Until tomorrow they still go to pay homage to that deity. The deity. Ani Onitsha. They call her Ani Onitsha. A she. In translation land of Onitsha. They said she protected us and made sure Nigeria did not harm, did not come to Onitsha across the river. It was when they came in from the north that was when we ran away from Onitsha. I don’t even remember the date but then we went into the hinterland. We stopped in, first, a town called Oba. Then later we moved to, I think Ihiala. And then from Ihiala now we later moved to Ajalli.

I was in Ajalli until the war ended. We were there until the war ended.

Well, the first time we moved from Onitsha to Oba. We drove. Things weren’t that bad yet. Then from Ihiala, to Ihiala we still had vehicle then to Ajalli but then the vehicle did not leave Ajalli. It was jacked up and placed on stones. That was where it stayed till the end of the war. Every other place we now went, we went on foot. And even after the war ended. We walked from Ajalli back to Onitsha. It took how many days but then, yes.

When we left Onitsha, we left with some provisions and food items that we had in the house. Nobody knew how long it would be. We didn’t even take all our goods. We just took the most essentials things and so as not to the burden the car. We just took a few things and we left. Everybody thought it won’t be long and we’ll be back. But then it started dragging and dragging and dragging and the food finished. Now, as refuges, we didn’t have land. So I now had to go and work on the natives’ land where we were staying. I went to work in their farms for them.

At a point there was one kind woman. A kind neighbor. She gave us a small plot where we could plant vegetables so for vegetables near her house, we go there but then I go to work in other people’s farm as a labourer. And then I go down to the river. They have this raffia palm. I cut a lot and make thatches for houses, sell. Then I was already very good fisherman even before– because my mother comes from a riverine community where they are all fishermen. So I go to fish. We supported my family. The fish I caught, what we can eat, we eat, what we– rather keep some to eat then sold some then, my mother would buy cassava from the natives. We would peel then take it to a grinding machine where they grind and we come back and make garri. So we became a family of entrepreneurs on food. We make the garri, we sell some, and we eat some.

…the bombings were on civilian targets

I go to work for people. Sometimes there wasn’t that much money anyways. Very often we were paid in kind. Usually if I go to work I’m sure the owner, according to traditional system, whoever you go to work for would feed you for that day. Sometimes when we’re going– the natives also knowing that we were refugees, sometimes they were quite generous. They give you a few tubers of yam which you bring back and that was how we managed and survived.

The air raids. The town Ajalli was headquarters of Biafra 82 Brigade or so. I think, Biafran 52 Brigade was headquartered in Ajalli. It attracted attention of Nigerian jets and every time when it comes, we didn’t have any anti-aircraft. People weren’t informed. Some people will come out with their double barrel and be shooting those and then some soldiers they would shoot up and of course those of us with some little training knew those were ineffectual. During the civil defence training, we were being trained already how to take cover so those trainings at the early time now became useful and some times people were afraid what will happen so they didn’t go to market or anywhere. In the morning they would go inside the bush to hide because the bombings were on civilian targets.

Anywhere there is a congregation of people, it could be bombed.

I can’t say for sure whether they were aiming at the brigade and made a mistake and it landed it in the market. I don’t know. But what I knew was that bombs dropped in the marketplaces and in schools. Some schools were used for- all soldier’s barracks were schools anyway. But so also refugee camps. How they can distinguish which is a refugee’s camp and which is a soldiers’, I don’t know.

I don’t think Nigerians really cared.

At least the killing from the North continued also the same indiscriminate way.

They continued killing us and some very funny things during that period. There’s this belief that if you put on a white shirt, the pilot could see you from up and so– if you were wearing a white shirt people would mob you to remove it or they will tell you, “Get away from us. You want to kill us?” that the pilot will see you with your white clothes and come. Well, those are the lighter aspects of it. As at that time, it wasn’t a light issue. It was a very serious matter. It was a matter of life and death. Now, when you remember such things you can smile.

When we were being evacuated, my grandfather had an older brother. He lived some distance from us. The person that organized the transport that took us out was my grandfather’s older son. That is my uncle. My father’s older brother. He brought a vehicle to take us out of Onitsha. My grandfather refused to move but I took my parents out. Took them to that last station where- then I came back to Onitsha because Onitsha hadn’t fallen by then. I came back to Onitsha.

Many of us with the memory of what happened in the October invasion were ready to fight again to defend Onitsha.

We were already making out network, reviving it for the defence of Onitsha from the Northern attack.

But this time around it was really different.

When the attackers crossed the river it was stealth. In the night, nobody heard anything. I think they probably floated their platoons or their badges and by the time we knew what was happening, already they were in the banks and the beagle was blowing inside the city. But this time around because they were fighting their way down from the north, they started shelling the city.

It was the shelling that drove us out. My grandfather was still there. Even for many families, they took out the men, the women, and children and their men came back to defend. Irrespective of whether they are soldiers or not. That is every young man wants- nobody was ready to give up just like that. So we came back now when the shelling was becoming intense, we decided to evacuate the older people. My grandfather was there.

There’s a neighbor of ours who had a car. He was living in the southern part of Onitsha near the river bank. Since after that 1968 invasion. They never went back because now the federal troops were shelling the shore areas. They pulled back to the inland part of town. All of us were staying in one of my grand uncle’s place. It was from there now that we decided to evacuate, my grandfather and my cousin’s grandmother also. That’s the mother -in law of that my uncle. They were staying there also, to take them out.

…how can there be such infestation of worms especially among children…

My uncle’s mother in law refused to leave. She said she would go and stay- there is a church- their church somewhere within the city there. That it looks like their prophet in their vision said Onitsha will not fall. And they had faith in him so they were trooping to that church. I understand a massacre occurred there when the federal troops took over Onitsha. All of them were packed there densely. But, then my grandfather, when we came near where his older brother– his older brother was still alive, my grand uncle. He was still alive. So my grandfather said he can’t leave his brother. He can’t leave without his brother. That it doesn’t matter, let us go that he would go and stay with his brother. Well, his brother had two grown up children but then I don’t think any of them was in the position to organize transport for him. One of them actually was the one that drove the vehicle that took out my grandmother and other people to Ajalli. I don’t think he came back. He stayed back there.

My grandfather decided to go and stay with his brother. That was the last we saw of him.

My father already you know how he died. My grandfather went with this brother. We left him behind. And after the war when we came back, my grand uncle’s house was burnt and it was in ruins and we didn’t see anybody. We didn’t see their bones around so probably they were taken away to another location where they died but there was no record so we don’t know what happened to him.

Kwashiorkor. I can’t remember exactly the first time I saw it but I remember the first time I heard the word that described what was kwashiorkor. I haven’t seen children with yellowish hair, protruding bellies and my mother believed it was worms. So they treated them for worms and sometimes actually they pass out worms but it wasn’t on such a massive scale.

We started wondering how can there be such infestation of worms especially among children like that?

Nnamdi Onwualu. Photo by Chika Oduah

And we didn’t know it was kwashiorkor. It was when I got to- there’s a refugee camp near where we were staying. Sometimes, when we made the garri, we take what we will eat then sometimes we take some to go and give the people in the refugee camps. We were lucky. We had family friends who sheltered us. Those who had nobody stayed in refugee camps. Our situation was a little bit better. When we make the garri, we now take to go and give them. When we get there, you now see these children with extended bellies and swollen legs.

It was at that camp that I first heard the word kwashiorkor. They said it was lack of protein that was causing it. I heard one of the officials who was telling mothers to try to source protein from vegetables. There were a number of vegetables they said could help, including cassava leaves. I don’t know whether that was true or not but we started looking for cassava leaves, also looking for protein to stave off kwashiorkor.

One thing that helped my family was that I was a fisherman. I travelled many miles to some nearby towns. I go there to fish and then I come back. I go very early in the morning—no, I go overnight, set the fish traps and hooks then go very early in the morning to harvest. That helped us a lot.

Well, when the killing started in the north, we know they were killing Igbos. What the aim was, I don’t really know. But then by the time they had been killed and they ran away and came back to the east and now they declared a war against [Nigeria] and came, of course, I believe what they [Nigeria/Northerners] wanted was to wipe out the Easterners.

…go kill them and take their property

However, what made it even more certain, my mother spoke excellent Hausa. My family- Hausa was my first language before I came back. They understand Hausa very well. So when you tune in to the Nigerian station, there was a song they used to sing on the radio in Hausa. I don’t understand the words, “Muje, muje [let’s go, let’s go]” something like that. My mother said it means “let us go kill them and carry their property away.”

It was sang in open radio. If BBC had Hausa service, if they tuned in, their translators would have been able to tell them what they were singing. It was their mission statement. I believe they wanted to wipe us out. They just didn’t succeed but that was what they wanted to do.

Ah, we had a lot [of Biafran army war/propaganda songs]. We had a lot. We had a lot.

That was one of them. [Laughs] Well, it starts [translates as] eh, the country is devastated. Who is responsible? Gowon. Then, who is the sinner? Gowon. And what is wrong? Gowon.

Well, this is a taunt, that Gowon wasn’t educated and then gave himself colonel and this is against the rules of the army. Then the second line, says Gowon is an infidel. He doesn’t know God and he gave himself general and this is against the laws of the church.

[Laughs]

Well, these were taunts. Then, of course there is a follow up to that:

That is, Biafra rise up. War against Nigeria. Why? Because they are really the infidels that do not know the God that made them. That is from their actions.

[Gowon] was the embodiment of the Nigerian regime [so there was intense dislike for him among the Biafrans]. There was one Biafran song that says all I need is a bullet for Gowon and the war is ended. One bullet for Gowon, and the war is finished. One bullet for Gowon, and the war is no more. Every Biafran fighting is fighting for his nation. Every freedom fighter, is fighting for survival. There are so many of them [songs].

[Laughs]

[The killing of Igbos] wasn’t pronounced from the West. It was less pronounced in the West because in the West- of course there will always be people who would cash in on the situation, but it was mainly carried out by Hausa soldiers also who were posted to the West.

A lot of times, the native Westerners hid Igbo people and helped to smuggle them out. Of course, it’s not general. There will be occasions where they will come and give information to those Nigerian soldiers, especially where they want to loot their properties because one of the greatest advantages for them was to take their property.

…run like hell

Even in their songs, like my mother said, to go kill them and take their property. They continued so those who gave information against them in the west, they did. It wasn’t on that kind of organized scale as it was in the north.

In the north, your neighbors, everybody.

In the west, sometimes some neighbors.

“Biko, they are planning something, run like hell.” Sometimes, they will shelter them and then smuggle them out. So it wasn’t the same thing. The Northerners wanted us dead.

We know the Northerners, Hausa people, wanted us dead. We didn’t have much quarrel with Yorubas.

Although some Yoruba people were killed even in the 1966 coup but they didn’t organize that kind of planned execution of people. It wasn’t like that.

[My relations who were killed] weren’t buried anywhere. No.

We lost a lot there because all those souls that weren’t buried by our culture, by our tradition, they were still hanging around. As a matter of fact, many of them including my father, kept disturbing to have their funeral rites done. He didn’t appear to me but [appeared to] my aunt, his young sister.

Many of them [souls] were still hanging around. Those who had the experience [of seeing ghosts] said it. My father, for instance, appeared to his younger sister, my aunt, many times over his funeral and as a matter of fact, in my town in Onitsha for instance, looking at the number of people that need to be buried whose funeral rights have not been done. The Obi in Council, that’s the Obi of Onitsha, that’s the king of Onitsha, with his traditional council, decided to hold a general funeral right for everybody that was not accounted for. [It took place] immediately after the war. Sometime in January, I’m not very sure of the month but it was in 1970. The general mass funeral.

Well, in the immediate period it satisfied some but so many still didn’t buy it. We came back again and started again individually. Those that lost people individually started again burying them, giving them their proper burial rites. As a matter of fact, my father for instance, we didn’t do his funeral rites until 2010 because we were children and there was nobody to do it. I had to go to school, finish, and start working and not too long ago then. 2010 that was when we did his funeral rites. And within all this time, my aunt kept saying that the man is still waiting.

Probably because I grew up mainly with my grandparents, he didn’t have that connection to me. But eventually when I did, I took a bottle of Schnapps to his grave and called him and said, “I have paid the debt I owe you. Go in peace now.”

From that time my aunt said he didn’t come again. In a way, we lost a lot but those of them who still hung around also forced us to remember what our culture and tradition is and those children who were born during the war or after the war, who didn’t really understand. It gave them an opportunity now- when we started burying those people that died- it gave them an opportunity to catch up with our culture and bring them back as Igbos, as Onitsha people.

They are Nigerians [the ones who claim that the suffering during the war, particularly in Biafra, as bad as we say it was]. There was no suffering in their area. They were the people that blockaded the East so what kind of suffering do they want to see? There was no suffering in their area.

The suffering was on the people that were blockaded. The suffering was there. My wife was a girl at that time. It got so bad at a time she was almost evacuated to Gabon to escape kwashiorkor. Many of our children were lost in Gabon. They are now Gabonese citizens. Some in Ivory Coast. Their mothers and the parents that had them died and nobody knows about them anymore. The mothers were ready to give them to aid workers, “Please, just take them.” Sometimes they couldn’t even have a decision because they themselves were too weak. As the mother is dying, the aid workers took the orphaned child. Some were older, many were babies. They were taken to Gabon, to Liberia, those places. They grew up there, they didn’t come back because nobody has a record of them.

I believe if you pursue this research in Gabon you might probably trace what happened to some of them. Or Liberia. Because they [the government of Gabon and Liberia] recognize Biafra. The aid agencies operated from there. It happened that way. The Nigerians that say it [the suffering we endured] was exaggerated, well they didn’t even admit that they killed anybody in the North.

…an unsustainable carnage

But the orphans and the widows, all of them were not casualties from the war. A lot of them were orphaned from their fathers being killed in the North. My wife, her father was killed in Jos, Kura falls where he worked.

Some of the people that saw him last, were their neighbors that killed him. If you are asking such a person, would they admit that they- no. They won’t admit that they killed. They will tell you that it is exaggerated.

…At the end of the war Gowon said there was “no victor, there was no vanquished.” That’s just a slogan. That was just a slogan. But I believe even Gowon himself, in the midst of the killing of September of 1967 I think even he himself said that this is too much. Probably they planned a little and they lost control.

The killing was so massive. I believe it’s out of shame, out of some twinge of conscience that they had to say no victor, no vanquished. The Biafrans were vanquished. They were vanquished long before the war ended. The killings that deprive them of their lives in the North. After the war itself, in restructuring the economy, they were further– how do you say it? Even the money they had was taken away from them. No matter how much you had, we were just given £20 and then they embarked on the indigenization of Nigerian economy.

…Some people will say, “Eh, it’s exaggerated.” Oh well. Exaggerated. What’s exaggerated?

Hunger?

They didn’t see anything and besides, anyway, communication then wasn’t as it is today. But ask independent observers from Europe who came. Go to the Catholic Church. Find out from characters, they flew, the risked, they flew to bring in supplies. They risked their lives. It was what they saw on ground that made them risk their lives. They knew the scale and magnitude of it. Anybody that says it’s exaggerated is one of those are still hiding away from their conscience. They don’t want to admit the atrocity they committed. That’s the only person that can say it’s exaggerated. It was atrocity without doubt.

It was a big relief when they announced that the war was over.

It didn’t happen suddenly like that. Some things precipitated. There was this elder statesman, the first president of Nigeria – [Nnamdi] Azikwe who was in Biafra then. Actually I believe he was instrumental to the recognition we got from a country like Tanzania. They were personal friends with President Julius Nyerere. So he would have told him exactly what was happening and part of the strategy was to get these recognitions. Well, I’m from Onitsha, so I’ve heard some version which weren’t written anywhere but anecdotal evidences and discussions that came from the mouth of the sage and those around him. The idea was to use the recognitions that they could get to go to the peace conference and demand for confederation in Nigeria. However, that’s where I fault Ojukwu also. On the eve of the battle of the delegation, the lead of the delegation was changed. He put his cousin, [Christopher C.] Mojekwu, instructed him that Biafrans sovereignty was not negotiable.

So Dr. Azikiwe, all the diplomatic shuttling he made was for nothing. So Azikwe crossed over to Nigeria. When we heard on the news that he had gone to Nigeria and Gowon has received him in Lagos, we knew it was a matter of time before the war would end. Because he can’t continue. It was an unsustainable carnage. Ojukwu that said fight to the last man, when it came to his turn, he jumped into a plane and escaped to Liberia. Many of the young today especially those agitating for Biafra have no idea actually what Biafra was about. Or what even made it fail. They have no idea. It is a pity that we are not teaching Nigerian history officially in school otherwise it would have helped the younger people to understand and be alert what is happening and say to themselves, never again.

*This interview was conducted by Chika Oduah in Nnamdi Onwualu’s home in Abuja, Nigeria.