My name is Elizabeth Ugonwa Anyakoha. I was born June 18, 1948 in Imo State. Arondinzuogu is the town.

Professor Dr. Elizabeth Anyakoha remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

Yes. Ehm, 1966, I was 17 or 18 years. I just took my West African school certificate. I took it in 1965 and in 1966, it started. So, I was out of school but, I got employed in the then-Ministry of Agriculture and my group, we were sent to the School of Agriculture to be trained as Agricultural Assistants. That was in Umudike. The then-College of Agriculture, Umudike, under the Ministry of Agriculture and we had a one year program after which we were posted out and I was posted to Awka – Ministry of Agriculture in Awka and we were there very briefly before the Nigerian soldiers came along and we had to trek. If you know where Awka is, well within the now-Anambra State, so we trekked from Awka to Nanka. That is from presently Aguata local government.

Yes. That was when [the war began], well when we saw the war, it was on and then, you know, the soldiers, the Nigerian soldiers kept coming and any town to people had to vacate and become refugees somewhere.

Because I just started working, I was traveling alone but in the company of people. Yes.

I didn’t see them [the soldiers, actually enter Awka]. But, we heard the gunshots.

I personally, because my mother had warned me that, in fact we were living in Umuahia. That is the present Abia State and I was posted to Awka and she told me if you just hear the gunshots and the bombings and the rest of them, and people are moving, move, don’t pick anything and like a child, I obeyed. So, when it started, I moved along with people. So, it was like ehm, people flowing, you know, away from Awka and moving to where we didn’t actually know.

I was trekking. Yes.

It was, I guess was, it might have started in the night but, it was in the morning that we all left. I left along with others.

Hmm, I can’t remember [the month when this happened].

…mothers carrying their infants in basins

We were staying in Amawbia. Yes. In fact the house I was living in was directly opposite, close to the road and the opposite side was ehm, ehm, the prisons. Yes. Prisons and I think it’s still there.

I was living on my own [in Amawbia].

Yes. It wasn’t really a flat. Well, studio flat, if you like. Just one room. I was 18. 17 to 18.

People were shouting. People, it wasn’t easy. People leaving their houses, their belongings. You could see people traveling. You could see mothers carrying their infants in basins, if you like, on their heads and running.

Professor Dr. Elizabeth Anyakoha. Photo by Chika Oduah

I didn’t see smoke. It was still coming. They were not, well, from my own perspective, they were not yet there but they could be minutes away from the place.

I was just walking on my own but in the crowd. But after sometime, somebody met me, somebody my parents, precisely my father, sent somebody to go and look for me and that person was on bike. I think [it was] my father’s cousin. Yes, from his maternal family.

They [my parents] were in Umuahia, Abia State.

Without the war, I was OK but with the war, it was just that because if one had stayed and the military, well, the enemy soldiers caught that person, I think that person was in trouble because some people of my age, that time were got themselves, found themselves married, compulsorily and I hear they were calling the Ojukwu tomatoes. You know, so, it was a traumatic experience for people of my age who were caught unawares and forcefully married by the soldiers.

I wasn’t carrying anything [as I left Awka]. In fact I can’t remember. They only that pained me when I came to myself was that I didn’t carry my album, my family pictures. But, I think I just took a bag with few dresses inside because my mother warned when it starts, don’t carry anything, don’t look for anything. Just keep moving. So, I obeyed my mother and I guess it was OK because if I had looked at the belongings, I might have been late in leaving the town.

It wasn’t necessary [to lock the door to my flat before I left] because they were going to invade the whole place.

In fact, I didn’t know what I was thinking about. I had never seen war. I had seen war. I’d never thought about it. In fact, coming out from the secondary school, we didn’t even, I personally, didn’t know how much the problem we were, I was going to face. Or the Igbos we facing.

Actually, I stayed, from Awka, I went to Ekwulobia. Yes, that is, right now, the capital of Aguata local government. That was where I went to and the office I was working in was also transferred to that place, the Ministry of Agriculture. I was engaged in gardening. I was producing vegetables, onions, and ehm vegetables.

We were told, I was told in the office, yes, we were told [that the office would be transferred] and I knew the whole office, the whole people were moving there and we know the office was, I knew the office was going to be there.

…the anxiety that came with the war was too big

That night, I got up because of the person who picked me, because my father’s mother, that’s my paternal grandmother was from Aguata local government area. So, my father had some relations, so, I slept in one of the relation’s houses and that was where I stayed until they helped me to find another room where I lived throughout the war.

I had a small room with a family. [That’s where I stayed during the whole war.]

I was in touch with my mom, but my father was caught off during the war because he was working with the then-ENDC, Nigerian, Eastern Nigerian Development Corporation. So, he was working with them in Bende. So, that was where he was working in their agricultural sector too, and during the war, he was off. He was there. He couldn’t get to home. So, we were not in touch with him for the whole of the war period. But I was constantly in touch with mother.

I could travel. I could travel to, from, from, ehm, Aguata to my home, Arondinzuogu was not far and there were still some vehicles moving around that could take you to, take one close to home and then trek the rest of the distance.

It was never, Arondinzuogu was never invaded. Refugees came in.

I was working [throughout the war] because I was working in the agricultural sector, so, we were producing little, little food.

Ehm, during that period, with the group I was working with at the harvest time, we harvested and took to the office, to the department and distribution was the responsibility of our superior officers.

We didn’t have enough [food]. We were not producing enough to give them [Biafran soldiers].

…you’ll see flesh, people’s parts of the body everywhere, scattered

My health was very robust. I don’t know, we were, I didn’t have need to take any drugs. Maybe because of the trekking, wherever you were going we were trekking. Yes and the anxiety that came with the war was too big for any illness to come near because you will sleep, it’s like one sleeping with one eye closed and the other one open because very early in the morning, the air raid, that is the air, they came to throw bomb, you know, and because where I was living was close to Uga airport. That is one of, I don’t know whether it’s even the biggest or next to the biggest Biafran airport. So, they were coming every day.

You wake up in the morning, you won’t even finish praying and the air raid will start and we will run out, go into bunkers or even before you get there, it has started and we were seeing them, you know. It will still be dark and you will see the bomb dropping. At times, we thought oh, our people have shot down the plane. We wouldn’t know it was their canon, you know, coming down.

Professor Dr. Elizabeth Anyakoha remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

At times, we will even see the people in the aircraft. Well, the people I saw were white. They were not black and when it was like, they were hurling the bomb out of the plane, and the planes were flying bombers, jets, flying very low. Sometimes like under the trees, palm trees and you will see that. When they finish, it’s after the air raid, you’ll start hearing people yelling and crying and when you go out, you’ll see, at times, you’ll see flesh, people’s parts of the body everywhere, scattered.

Some people wouldn’t eat meat anymore after seeing human bodies

Oooh, it was terrible. Terrible. It was, in fact, I don’t know how to describe it, you know. So, it was bad enough because you wouldn’t know who would be the next person and the person you were sitting with before it started could go, could be attacked.

Professor Dr. Elizabeth Anyakoha’s hands. Photo by Chika Oduah

…you know, because of our belief in God. I have been a Christian and I believe in prayer. I believe God was in control. In fact, it was faith-based. My ability to have survived was faith-based and working.

You know, if you keep working and working and working, and then you go to sleep and you wake and you pray, and the enemy comes and throws the bombs, and then you run around, at times, you will lose appetite, if you have food to eat, you won’t even eat. Some people wouldn’t eat meat anymore after seeing human bodies and parts everywhere.

We didn’t even see meat [to eat].

[Chuckles]

There was no meat. So, the thought of eating or not eating, you know, it was ehm, I think relief, stockfish here and there occasionally. So, there wasn’t much meat to choose to eat or not to choose to eat.

Actually where we were, we didn’t experience the absence of salt because eh, these relief organizations and as somebody who was working, occasionally they will distribute some salt and even milk and in fact, I’m living just on my own. At a point I took my baby sister. I just had enough and even to send to my mother. Yes.

My mother was very good to his family, too. She had all she required in terms of carbohydrate to sustain her. She was planting, growing maize, yam, cassava, and the rest of them, vegetables. But, what they needed was salt. Salt was the important thing that was not there. I sent salt. If one sent salt it meant a lot. When I give to her, she even had to share to members of the kindred.

…just the head of the husband

We were told to lie low [to protect ourselves from the air raids]. I came out of the house, that compound we were living had a bunker which was nicknamed Ojukwu bunker. So, we will all go there. At times, one may not be able to get there before the bomb lands. We stood by the trees or we went flat.

I was not [involved with the war effort]. I was in support of Biafra, yes.

I saw the injury. I saw what was happening to the Igbos. I saw people who came back widows, orphans. In fact, there was a woman that I don’t know how it happened but she had to come back to Umuahia at a point with just the head of the husband.

So what, is it pogrom? Yes [pogrom], I mean, nobody could have seen such and would not support Biafra. In fact, I supported Biafra. I think, I don’t know. My family did and ehm, we the youth, I was still a youth, you know. Ehm, I supported Biafra, yes.

The nearest death experience was the bombing episodes that occurred everyday. Every, not just everyday like that. In the early in the morning and in the evening, twice a day. It was bad enough.

[We had to lie low or go into the bunker.]

Professor Dr. Elizabeth Anyakoha. Photo by Chika Oduah

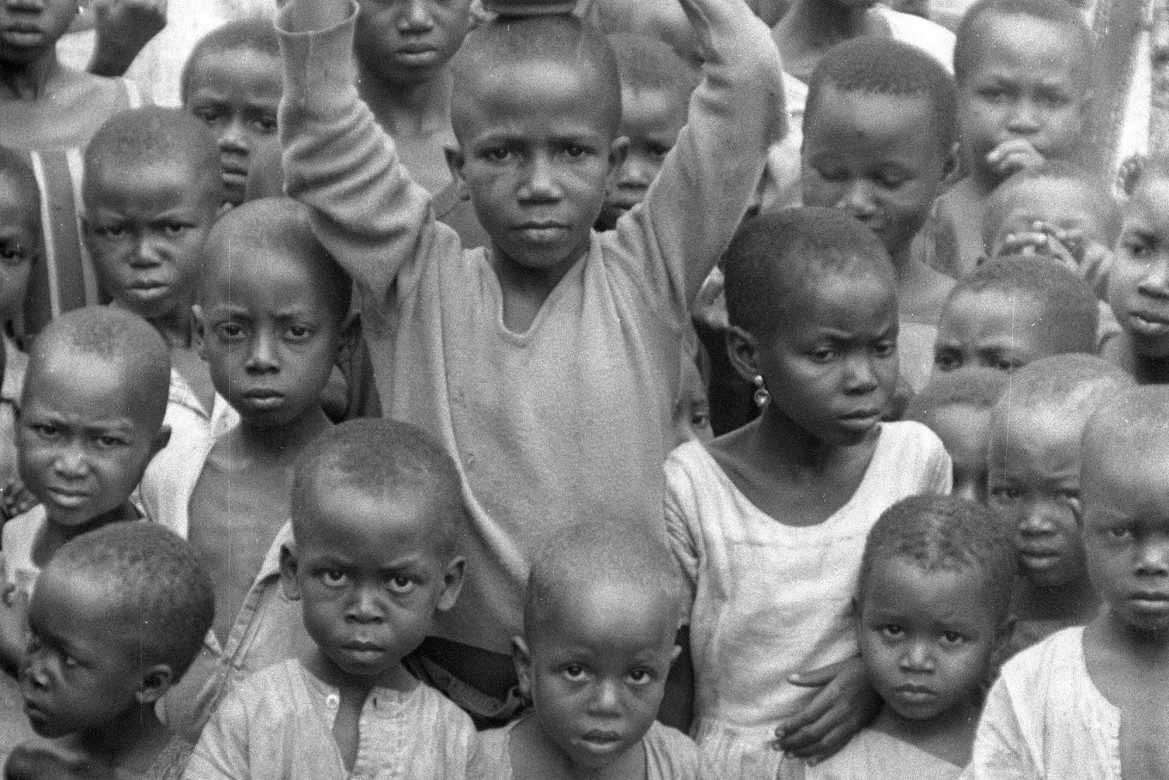

Nobody that I knew was killed but I saw human beings that were killed. You know, it was like a refugee camp was there and people came from different parts of the then-Nigeria and people mixed up. You wouldn’t even know who was who but, we were all moving together. Somebody would die. So, I saw people die and sometimes the young, the soldiers that are young people, too, who came from the war front and you’ll look at them with their heads shaved looking like coconut, you know. So, ugly sights and experiences.

It was bad enough

In fact, when it was said that [the war] was over, we were confused. We were not sure it was true. I was not sure it was true. I was not sure but I saw people moving around but I knew I had to be where I was. I didn’t run around or move to anywhere because it was possible that if a young lady like me left where I was I wouldn’t know whether I will meet the Nigerian soldiers and if one met them, if I met them, it could have resulted in “win-the-war marriage,” instant marriage without consent. So I was where I was until I became so sure that it was over.

Then, I left for my home. Trekked part of it and ehm had a transportation, this long trailer. In fact, I didn’t know where it came from but we entered the trailer, I entered the trailer, very mighty one. In fact, somebody helped me in and when I got nearer my home, they brought me and I carried whatever I had on my head and went to my father’s house.

My immediate sibling then, was conscripted into the army.

Christopher, Christopher Chukwu of blessed memory and my second brother [Albert] was also conscripted. They both survived the war.

The first one, my immediate younger brother was conscripted first and became a bodyguard to somebody. I can’t remember the name of the officer he became the bodyguard of and they were in Okigwe and the second one, I don’t know where they took him to because that time, parents would hide or young boys of their age were hidden near the streams to avoid being conscripted. I can’t actually remember how their cases went. But, they all came back at the end of it.

Every day was bad but, ehm, it’s not a very particular day. I think those days of bombing, they all stood out to me as bad enough because you will see dead bodies and you’ll see blood and they were human beings.

I didn’t have any experience that was different on a particular day but because my routine was just wake up in the morning, pray, go to the farm, do some farm work, come back, report to the office occasionally. It was like a station service that I was doing.

I was getting some salary. I would say because I was earning some income. Though it was small but I was earning something.

[I was being paid in] Biafran money. I didn’t see Nigerian money.

If you were around, you would just, I don’t know. It wasn’t much. That was the beginning salary of a school cert holder, GCE so it was not much. I think it was in shillings. Biafran shillings but then, I don’t know what I needed money for. I wasn’t going to buy dresses or anything. I just had, what I had before the war in terms of dress was what I had throughout until the end.

Professor Dr. Elizabeth Anyakoha. Photo by Chika Oduah

I had to some food items. But, once you have salt, you know, because when you cook and you don’t have salt in the food, I mean.

Oh we heard from [my father] from him few weeks after the end of the war. He came back. He staggered home. Because he was cut off, though he was not hungry. He had enough food to eat. You know I think during the war, I and as many other people we focused on our basic needs – basic needs, needs that helped us to survive. We were not looking for any extras. Primary needs and no secondary need.

*Professor Dr. Elizabeth Anyakoha granted this interview to Chika Oduah from her home in Enugu State, Nigeria