Laura Onwualu remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

My name is Laura Nwando Onwualu. I was born 1954 in northern Nigeria, Plateau State, Kura Falls.

I don’t remember much about the Nigerian-Biafran War but I remember then I was in primary 6, 1967 or 66. Yes, 66 -67 No, then, there was a time – they started teaching us a song, you know, it says it is going to be our new anthem for our new country, Biafra. So we were learning the song. What we are going to do with it we don’t know but then we started noticing people in the north – because then I was staying with my grandmother in Onitsha [in the Southeast] – we started noticing our family members in the North coming home [to the Southeast] you know. We don’t know they came back telling us stories of killing in the North about how they will come to the house. The Hausas will come to the houses, kill them you know especially the men and my father came home with my mother because they were in the North. My family came home. Though my father wasn’t killed. He was on leave [from work]. He came home and they were telling me stories. One afternoon my mother was in the market. We were home and people started running and I was very young then. I didn’t know why they were running. They said the Hausas have crossed the bridge and that they are coming into Onitsha.

We were hearing gun shots and bomb blasts and all that so I gathered my brothers and started running with the neighbors. We didn’t know where we were going. We left the house and we were just trekking and people were falling and people were crying you know because they couldn’t see their loved ones. My mother came home looking for us you know. Eventually she found us. Then my father had gone back to the North because after his leave he had to go back and we didn’t see him again so.

“We were hearing gun shots and bomb blasts”

Yes, after his leave, he decided to go back because then he was working with the white men. He was persuaded not to go back because of the killings [there in the North] but he said no. He just wants to get there, take permission from his work place and come back [to join us in the Southeast in Onitsha] so he left one morning and then we never see him again and that was it. So eventually somebody came to tell us that he was killed. He was killed actually with some people that, they were to board the train, that was September 29, 1966, they were to board the train coming back to the Southeast from Jos, Bukuru precisely. They were waiting for the train at the station that night to come to the Southeast so these Hausas, they came and killed all of them there. That was how we never saw him, my father, again till date.

“That was how we never saw him, my father, again”

Yeah, I was very close to my father you know, but the killing I didn’t really very much feel it. I just knew that I lost him, but I couldn’t see him, you know. He told me he was coming back, because then I had an exam. There was an exam I had, he told me that he was going to buy me a watch, if I passed the exam. So every day I had to sit in front of the house waiting for him to come back to buy the watch because I had passed the exam. I never saw him till just one day somebody came. I wasn’t even at home.

“He told me he was coming back…”

We went playing, I was very young then. I came in and I saw my mother and my grandmother and some other people. They were all crying, I was just confused. What happened? They said somebody said my father died. I honestly I didn’t even understand what death is all about. They were all crying because my father was an only child of my grandmother. It’s just that I missed my father. I never saw my father again so I never, I don’t know how I felt about it because I was very young. I don’t know what death is all about. It’s just that he told me he was coming back and I never saw him again.

It was just when I became an adult you know I understood what death is all about it. As at that time I never know what it was all about. I didn’t. I just felt his absence because I never lived with him. I left him when I was six years to live with my grandmother. I just kept thinking, you know, still believing that he will come back one day. He will come back one day and that is how we continued until I never saw him. So that was it.

Laura Onwualu. Photo by Chika Oduah

I remember the song that they told us would be our anthem. It goes like, “Land of the rising sun we love and cherish” I can’t remember the other stanzas but it went like that “Rising sun we love and cherish”, I can’t remember. I can’t remember it again. It was very long ago but it started like that “Land of the rising sun we love and cherish” that is the first stanza but I can’t remember the rest of the stanzas. I have forgotten and that was it.

I don’t know how I felt singing the song at the time. I was just singing and even at that time I don’t even know the meaning of what we were singing. It’s just that they taught us the song in the school to be singing and because we didn’t continue singing it because there was no school [during the war]. When we left Onitsha we stopped going to school [throughout the war]. There was no place to sing the anthem. Normally, it would have been in the school, maybe in the morning during assembly but as we left school as the war started there was no place to sing it anymore.

We were trying to survive. We were, you know, running up and down, from one town to another looking for shelter for days. Sometimes we will be in the bush hiding from the air raid. They will say “They are coming oh, Nigerians are coming oh.” We will run into the bush. We will be there maybe from morning ’till night and sometimes weeks on end because of the air raid, you know, trying to survive. Looking for food to eat. It was very tough for us because there was no money, no food so we were just trying to survive. We eat all sorts of things and then even with families that we never knew and all that, living in the villages, we don’t understand their languages and all that it was very tough and you know as a young person, I was very young then I had to take care of my brothers because I am being the eldest.

Laura Onwualu. Photo by Chika Oduah

It was very tough. It wasn’t easy for us at all, you know. Sometimes you will encounter snake, encounter scorpions and all that, you know. It wasn’t a pleasant experience, you know, because leaving from the town and then being in the bush— you have to go and fetch water in the stream fetch firewood to cook, fetch vegetables, do gardens and all that. It wasn’t pleasant at all. You will see children are malnourished. I wasn’t malnourished because we were opportune to live in a compound with a guy working with the Caritas so we were always having food and we make garri, make oil. I was even selling some foodstuffs so we were eating. Although we were not eating like kings but at least we have food to eat. I wasn’t malnourished at all.

I remember one of the air raids. We were just close to death, you know, the bomb fell just very close to where we were hiding where we were taking people. We were always told to take cover when we hear the siren. When we were just lying down you know the bomb fell just very close to us and our neighbors’ roof blown off and all that. We were very much afraid.

People pray and pray and pray you know there was a lot of praying. We were praying. We were very scared. And my mother, I know my mother is just such a fearful person, remembering that she has lost her husband and then her children now she is always afraid. For her, it is when she heard the siren for the air raid she start stooling (sic) in her pants. You know she panics a lot. She always fearing that she is the next person that will die. She will be calling God praying and praying. We are just small and we just looking at her saying “Amen, Amen” as she is praying. That was it.

The way she cries and shouts and all that. “Where are you?” Especially if she turns and she doesn’t see any of us, wow she goes, I will call it she goes mental kind of, so afraid shouting “I have lost my husband. I don’t want to lose my children oh Ndi Biafra oh Biafra Biafra Biafra Nigeria Nigeria.”

“The way she cries and shouts…”

I remember the trekking. We always trekked from one town to the other carrying the little things, you know, little property we just tie it on whether in a basket or in a bed sheet. Give us load and we will be moving from one city to the other and then I remember, I remember, soldiers marching in the streets and all that singing and all that. You know some of them you will see them with one bandage on their head. I remember once I was just by that village market I was selling stuff, I saw my uncle, one of my mother’s brother with a bandage on his head and they said he has lost his senses. I think the shelling affected his hearing so when I saw him, I cried. I just ran to him.

“…they said he has lost his senses…”

I held him. I was telling them that is my brother, so when he saw me he started crying, he has to follow me home. We gave him food and water so he decided he is still going back to his camp and that was the last I saw him. He didn’t make it, he died. He didn’t come back- my mother’s brother.

And they try to take us to Gabon but my mother refused, because I am the only girl. She said no she refused that I am not going. They had already gathered us with some of the children to take us to Gabon. I felt so bad because my friends were going but my mother refused me going and that was it.

There was one woman, one Mrs. Ilochi then. She was teaching us drama in that village where we are staying you know to keep us safe. They gathered us. As the refugees, they gathered the children there. They were teaching us drama and she told us then the time came for us to leave to go to Gabon.

My mother said no. She refused because she doesn’t want to lose us and she doesn’t know where they were taking us. Her fear is just she has lost her husband so she doesn’t want to lose her children. She is always guarding us because she doesn’t want us to go anywhere. I couldn’t go with them. They left and then I didn’t see them again because we left that city because of air raid and the war. When the war becomes so hard, too much – coming closer to where we were, we would go to another place. We lived in so many small, small villages in that time and then there was this incident towards the end of the war. We left Nkwerre, coming down to Okija. We were about to come home, so we came and we joined the family members and then they said that my grandfather was there with my uncles and all that so I was asked to go to market with one of my cousins because I was the only small person in the house.

Laura Onwualu. Photo by Chika Oduah

The others are adults, so on our way to the market they said that the soldiers are kidnapping young girls. I was about 14 and a half then to fifteen years. We were just young and these Nigerians soldiers saw me. One said that he is going to marry me and I said no. But then I said OK, if you marry me, but you have to come and see my parents. People were afraid that the man will kidnap me or whatever so fortunately for me by the time the man followed me home and saw my grandfather. He was afraid because my grandfather was very old then, you know. He has this fearful face.

He was afraid. He couldn’t say again by the time he saw him. He said OK “one Nigeria, one Nigeria, come up in-law, in-law.” He came up and they gave him drink and kola nut. After eating he said he’s going that he will come for me again. But immediately he left we had to leave that place because we didn’t know them. They were just picking girls anyhow. That was just towards the end of the war so we had to leave because they felt they may come back for me again. They may come with the other soldiers. They had to take me out of the place. That man was a Nigerian soldier.

The Nigerian soldiers, they were raping girls, you know. Igbo girls you know, young girls, and even married women and all that. They were raping them when they come into the city. They rape the young girls there take them away as wives and all that. That’s what they were doing then.

“…they were raping girls, you know”

I had no understanding at all why there was war. I have no idea; it’s just that we heard that they started killing people and we were running while they were killing us we don’t know – I don’t know, because like I said I was very young then so I don’t have any understanding. All I know was that the bombs were falling and the shooting, the gunshots and people were falling. As they are running you will see the bullet will hit somebody, and the person will fall dead and we will continue. They will tell us not to look back, we will continue running.

It was very fearful because, you know, it was so confusing. What is going on? Some days we will go without food because maybe where we are going we have not be able to see food or water to drink. We will just be trekking and be going. When you are tired, you drop whatever. We were all crying “Where are we going? What is going on? We want to go back to our house!” We don’t know what was going on.

Laura Onwualu. Photo by Chika Oduah

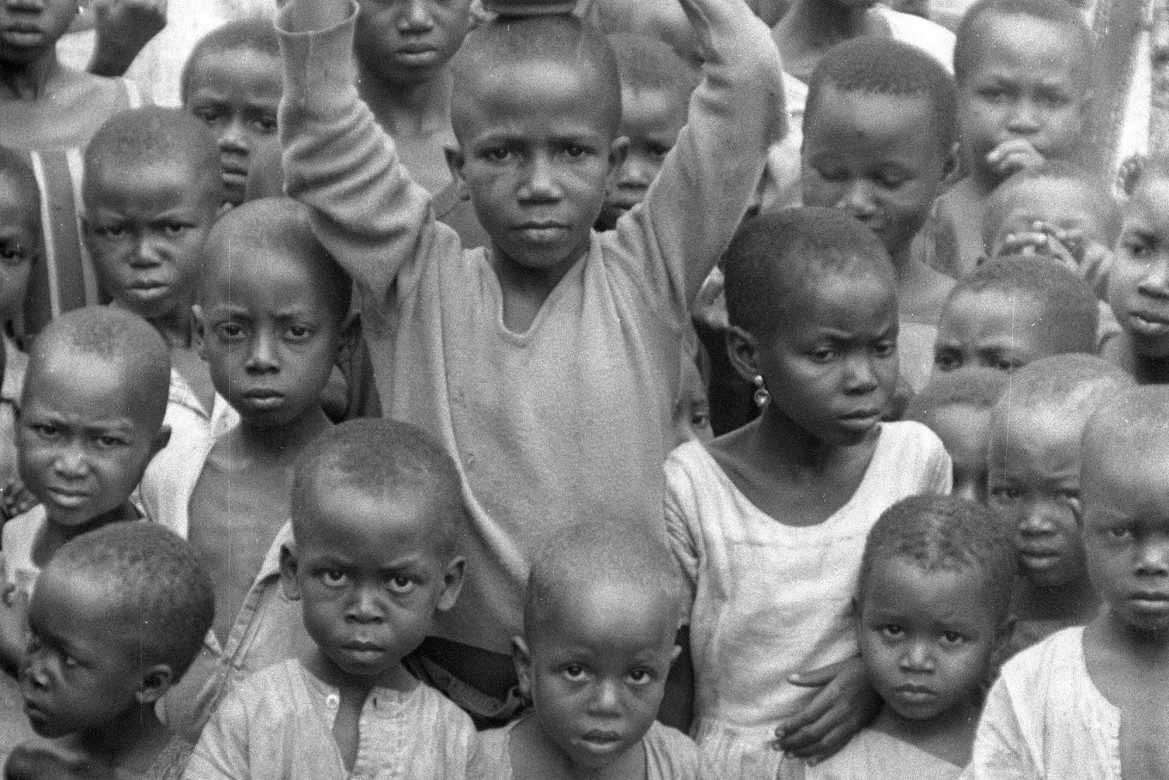

The suffering was so much. You will just see children’s ribs with their heads as stone colored. They said kwashiorkor and all that. People really suffered; some people can’t even find food to eat. Then we that had opportunity of having little food. When we cook we give out to people, we share with people who don’t have. A lot of people were not eating. The refugee camp, when you go to refugee camp, it was an eye sore. It was a pity. What you see, the children there, honestly it was so bad at a stage you will see these young women and they don’t have clothing to wear. They tie wrapper on their chest. Some people were using their petticoat as a skirt. All these young women you know, so it was so bad. People were looking like mad people. So bad. It was bad. It was bad. I remember after the war, immediately after the war when we went back to school, a friend followed me home, you know, and then six months later we came back she said “ahh what happened. The woman I saw the other day was not your mother because my mother lost a lot of weight.”

“The refugee camp, when you go to refugee camp, it was an eye sore”

It was so bad and you know mothers were sacrificing for children. I am sure that some days she goes without food to make sure that we have something to eat maybe once a day maybe twice a day. It was very bad. There was no food. There was no food.

Then, one morning they said the war is over, that we are now going back to Onitsha from where we were then. When we started moving, we were moving. We came down to Onitsha. We couldn’t even come back to our house because they say it is still not safe. There are bombs littered everywhere so we stayed in one part. My brother picked a three pence.That is what we ate with. lLuckily my mother speaks Hausa so we used that three pence to buy grains from the market. There was no more running. There was no shelling. There was no sound of guns and all that but the suffering continued because we had no food at all. No food. We came back in Onitsha. It was a dead place, no food, and nothing. It took us time to, you know, gather ourselves to start eating again.

Onitsha was a deserted place. So deserted, the houses, many houses was broken down and no roof, no windows and, you know, no property. They have looted all the property and you know it was dilapidated. Every place was just like a ghost town when we came back. Like a ghost town, nothing.

In all, my father died, my uncle died, my aunty’s husband died. I lost a lot of relatives in the North. My father died in Jos, my uncle was killed in Kano, my aunty’s husband was killed in Kaduna and another of my uncle died in the war. He went to war and didn’t come back and another of my uncle died in the war. Also he went to war as a soldier. He didn’t come back so I lost about six relatives, close relatives all six of them.

“…I lost about six relatives…”

My father was murdered; they butchered him. I still think about him because I knew my life would have been different if he had been around but I lost him and him being an only child, he had nobody to help us after his death and it was a real struggle for us to survive because there was nobody to help. Nobody. We had nobody. It was a big blow on us. I had to sacrifice my education for my brothers because they say I am a woman so I got to a certain level then I had to stop to help my mother train my brothers because there was nobody helping us. We had nobody helping us. My father’s death devastated his mother because she was never herself again until her own death. She lost her memory after the death of my father and she remained like that until she died.

“My father was murdered; they butchered him”

I pray that all these boys agitating for Biafra should just forget it because we are better off being one Nigeria than being Biafran. There is nothing and I know there is nothing in Biafra. Better to be Nigeria than agitating for Biafran states.

*This interview was conducted in Laura Onwualu’s home in Abuja, Nigeria

The story is so similar to my mother’s and her family’s in the Holocaust in Europe. At the end Laura tries to discourage Biafra from trying again. It is unimaginable for her that it will happen again. The killings, the starvation, the Death Marches, rape, pillage… more than we can imagine although all of that visits us in our nightmares from our parents’ stories. My mother used to say, “if there is a G-d in heaven, WHY?”

LikeLike

Hello Naomi. Dr. Herbert Ausubel also makes a comparison with the Holocaust. Read more about his observations here: https://biafranwarmemories.com/2019/01/29/i-identified-with-the-igbo-as-sort-of-the-jews-of-nigeria/

LikeLike