Obum Okeke remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

I am Obum Okeke from Anambra state. I was born in 1960.

The Biafran war. I was about six getting to seven, there about. I was in a primary school in Port Harcourt.

One fateful day, a group of soldiers entered the school and then educated us on how to take cover when the military aircraft comes to bomb. They told us that there would be an alarm. The alarm would be sounded from so that anywhere in Port Harcourt, you could hear it. So that once we hear it, there would like an announcement, “The enemy plane is around. Take cover.” Then we should all lay flat on the ground. So, we were educated and made to try it out and we tried it out. And you know, innocently we never knew it was going to be worse.

“The enemy plane is around. Take cover”

As a kid it was interesting, those drills. We never knew what was happening. I mean, when you were told to come out and take cover, when the enemy plane lands, or when we see the plane. It was fun in the beginning. We didn’t know what was to come next but just the following day after the drill, we came to school as usual and then a few minutes after the devotion, the soldiers- Biafran soldiers I believe- came in again and said we have to leave now. Every person. And then there was pandemonium. The principal called the school together and announced that we are vacating until further notice. I will not forget that phrase: until further notice. I had never heard it before. I loved the sentence and that was how we went home. And you know that time, there was no phone. We were crying, shouting, because there was pandemonium and then my father’s driver came and picked us up and we got home.

The first day the soldiers came, they were friendly. You know, they were drilling us on how to take cover not when they came the next time. The experience was frightening because you could see tension all over them. It was no fun the second time and then we saw even the headmaster running away with fear on his face. As a kid, it was an experience I will always remember not pleasantly, anyway.

Obum Okeke. Photo by Chika Oduah

At that very point, we didn’t know it would get so bad but the next day everything was happening in quick succession. The next day we were to leave. No, I think that evening. Yes, that evening we were to leave for Aba. We left to Aba. My mother and the rest of the siblings, my siblings, we left to Aba immediately that day. My father didn’t go with us so the driver took us in a car.

We went to Aba to an uncle’s house to stay there. We took refuge in Aba and then my father stayed behind in Port Harcourt. Actually, I left in my school uniform and with my elder sister. We just were rushed into a car and were driven to Aba. Many other people were actually leaving Port Harcourt. The road was rowdy. It used to be a very narrow road and many people were actually leaving Port Harcourt en masse. I remember seeing people frightened.

But my father stayed behind.

But I could see fear in my mother’s face and the faces of people I met around. There were checkpoints on the road. That was the first time I remember seeing a checkpoint. We got to Aba safely, anyway. Yeah.

“I remember the first time I saw somebody shot dead”

We got to Aba and then we were waiting to know what would happen next. We didn’t know what was happening because we were kids. We were happy play with our cousins in Aba. Unknown to us, my father actually had to leave Port Harcourt also.

I remember the first time I saw somebody shot dead. There was this horrible experience in my town and we had to twice. The first time, after about three months when we left Port Harcourt– Aba to the village. We had to leave my town again to a neighboring town where we stayed about two months and then we came back. Many people fell and died on the road and as a kid I saw these things. The second time when we were going, there were these sniper shots, when we were leaving that second time, actually. The Nigerian troops had entered my town. You know because the bullet shots you see people falling and dying. As a kid, it was not something you want to see again. And it’s not something I would my own kids to see again.

Nigerian troops entered my town early in the morning. The routine that time was to go to the bunker. We ate in the bunker, we slept in the bunker because there were these insistent bombardment from the Nigerian troops. We thought it was a usual day. We were in the bunker, unknown to us Nigerian troops had entered from Oka.

Was there even any Christmas that year?

And my town happened to be the very first town you meet coming from Oka. By the time we were leaving, they were already in my village. We just carried things and we were running. My task was just to carry my father’s suitcase full of vital documents. I could carry it and then were trekking. My old grandmother was really the problem and my father had to put her on his back. She was old, weak and apprehensive. The journey from my town to the neighboring town should be about seven kilometers or there about. My younger one was about two years old. Imagine making that journey. We were led by some military guys, Biafran military soldiers. They led us out of the town. And that was it. It was not fun at all. I remember it was close to Christmas, 1967.

Was there even any Christmas that year?

In the beginning we stayed in a school, camp there, before my father was able to sort out because as a young man he taught in that town. After about two days, we were given a home to stay. There was fear that that town will even fall. It’s not far from our town. The older men like my father will leave very early in the morning to the bush to hide because they don’t want to be conscripted for the army, Biafran army. We were left with women. The women would be fearing for their husbands.

I did have a little understanding of what was going on but not as much as I know now. All we knew was that people were killed in the north, our people, because a lot of them came back with sad stories. Cousins telling how their mothers, their fathers were butchered. So and then we hated anything North. We were made to see pains in their eyes and all these things. I mean, we were not happy with what was happening.

And then there was pandemonium

Some of them witnessed them being killed, slaughtered and telling you the story and you imagine the kind of human being who could perpetuate such a thing to fellow human being. That was the way we were seeing it.

At the time, did I even know what was a Northerner? We were not brought up to know this difference. Even if there was a Northerner in my class, I never knew. I saw him or her as a Nigerian. That was how we grew up.

Obum Okeke. Photo by Chika Oduah

It was really unimaginable

Port Harcourt was such a place that you could meet northerners. I never knew there were northerners or there were Christians or Muslims or this. So if there were northerners, there was nothing to show that there was this separation or demarcation, no. It never existed. I didn’t experience it. So when you were hearing about Northerners, I was asking myself, are they Nigerians, are they blacks like us– are they human beings? Who could be slaughtering people alive like that? It was unimaginable. It was really unimaginable.

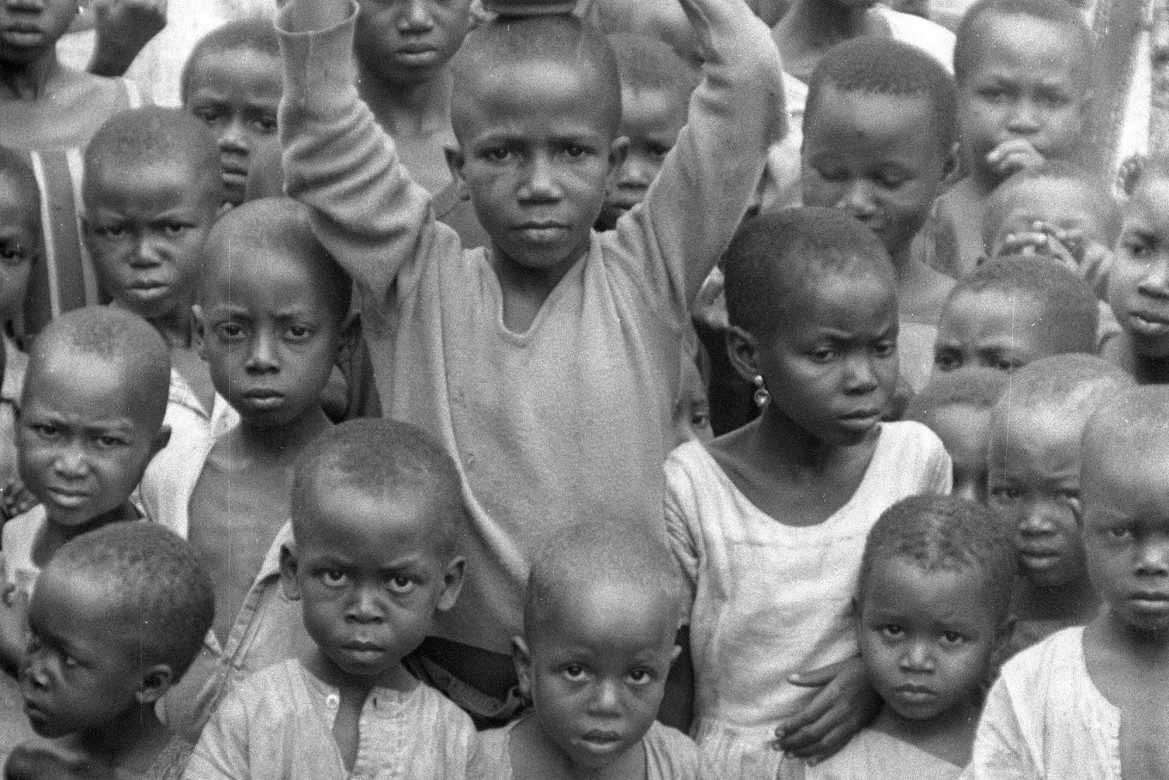

Kwashiokor. I saw it live and direct. I saw malnutrition. The kind of thing we see today in Somalia, I saw it. I saw it. Legs swollen, tummy protruded, people coming as low as skeleton you could count their ribs. Man, men, women, young, old, children. And the worst thing about this war was that even children were targeted. Women were targeted. Understanding what a war is today and a civil war for that matter, I think that issue should be revisited because from what I know now there should be limit to a civil war. But when marketplaces are bombarded, when homes are bombarded, when children, women are targeted, that should be something that should be revisited. There was no civility in the war. There was none. There should be a visitation to that.

“..children were targeted. Women were targeted”

When there was a blockade, when you could not find salt, you go to rivers to fetch the river salt to get salt to cook your food. If not for Caritas, the Roman Catholic Church, a lot more people would have died.

…we saw several skeletons of dead people

During the war, my grandmother died, my uncle died. Who didn’t die? Now when we returned to my [father’s] compound [after the war], we saw several skeletons of dead people. Skeletons, when we came back after the end of the war. We buried the skeletons. We buried them.

My father’s compound, flattened. When I mean there was no block on top of another block. It was a war front. War front. Completely flattened. A lot of people died there. It was a war front. It was an experience I would not like to see again. Inasmuch as I support the spirit of Biafra, I do not support the separation. Balkanization of Nigeria, no. Let Nigeria be restructured where people can develop at their own pace.

“It was not a civil war”

A lot of people died. I still don’t know why the world kept quiet. There was massive genocide. Ethnic cleansing. The idea was to wipe away a race. That was the idea, the whole idea.

It was not a civil war. If what civil war means is civility in war, then it was not a civil war. Children were targeted, men were targeted, women were targeted, and market were targeted. When you employ hunger as a tool of war, there is no civility in that war. So I’m able to say it was not a civil war. It was a war meant to wipe out a race. That is as far as I’m concerned.

*This interview was conducted by Chika Oduah in Abuja, Nigeria