My name is Venerable Professor Jacob Ukwuchukwu Onyechi. I was born in October 18, 1951. I was born in Awka, Nigeria. That’s in the present Anambra State. Old Anambra. It’s still Anambra State.

Venerable Professor Jacob Onyechi shares his Nigerian-Biafran War Memories. Photo by Chika Oduah.

In 1966 [when the pogroms started], I was at the Government Secondary School, Afikpo. That’s in the present Ebonyi State. Class 2 student because I got admitted there in 1965.

We were in the thick of the action

We saw all that [the killings of the pogroms]. It wasn’t a question of hearing. We saw all that because when the war started, the pogroms started because the normal transport to home is by trains and you may have heard that dead bodies were put in trains and shipped or transported to Anambra State, the former East Central State. So, we saw all that. We saw a few dead bodies. It was terrible and some students who came to Government College, Afikpo then from the military school, that was a school for training the military, they left their places and came back to the East. Some of them were sent to Government Secondary School Afikpo as cadets. So we saw them. They lived with us and they trained us in so many ways. We were in the thick of the action.

The dead bodies were put there. Some were without heads. Some were without bowels and it was an occurrence I and some of my colleagues went to view and that was terrible. As young men, we saw what we had been reading in the papers, hearing in the news as very very true.

We saw. Yes. I remember I said we were at Government College Afikpo, so, when those things started happening, there was a rush, in fact call it a mad rush to go and see whether what we were hearing was true and we saw all that.

We were given tickets to travel so we didn’t have to do it on many occasions. We needed to go and confirm that it’s true and subsequently school was closed because of the danger. We all have to go to our different villages.

Yes. We saw it, [once]. It was a question of loading the bodies into the trains and bringing them down. I wonder why whether it was for us Easterners to see our colleagues who were killed. I wonder why. But, it was horrific. That’s the best way to explain it.

Emotions were aroused and for who were kids then, that galvanized us. We went back home and we were not too young not to join the military when it started. So, on the Biafran side, some of us, because we were already big boys and we were up to it, we were asked to join. A few of my colleagues joined the military immediately. But, I had to wait a lot. My father was, my daddy was a pastor. We lived in the village and he pastored a village church. We were there until it became impossible to stay away. What I mean by impossible was that there was conscription going on. The Biafrans needed men and so, we called it conscription. In families, people counted those who went to the military and when it became impossible for us to stay, I joined the air force because in my father’s compound, my father’s church, in the parsonage, the air force came in and requested that we leave and they took over the church, school and we want to go into the town, into the village. My elder brother, in fact, I was bigger than he was then, went to buy family provisions and he was conscripted. So, he joined the army.

That was early 60…late ’66, ’67. The conscription started late 66 into 67. Yes. If your family decided that you had to go, you had to go. And it became difficult to get people coming on their own.

Let me put it right. It should be early ’67 in context. Early ’67. The pogrom was ’66. The war began June, you’re right, ’67.

I joined the air force, it was, I am not sure of the exact date but, I remember that it was when the air force came into Uga [in Anambra State, about 30 km east of the main Biafran airport at Uli, used mainly for military purposes, while Uli was for relief materials]. There was a strip, local strip at Uga and we were at Ezinifite [a town in Anambra State] and then when they came to recruit people for the air force, I volunteered. I went to the camp to volunteer and I was chased back a few times, twice, but, it was obvious that for my size, I couldn’t stay away from it. So, I pleaded and in the last attempt, I was taken. I think that was ’68. ’68.

I thought the air force was a lesser evil

I’ll tell you why [they kept rejecting my offer to volunteer]. Everybody knew my daddy was a reverend-in-charge and the air force officers knew us as family because they were always coming and coming around and were providing a few things and so, each I went there, they drove me away. But eventually, I pleaded that they should allow me as a way of escaping the enforced conscription into the army. I didn’t want to go to the army. I thought the air force was a lesser evil. So, that’s where I went.

They were preserving me that’s you know, saving you know, the man from the heartache that follows from, because a few of our colleagues who went into the army died. And I’ll tell you this because that’s what really happened. The military will bring back the dead bodies and bury them but they’ll come to my father’s church because he had to console them. He had to go and do the needful. So, they were preserving me, [laughs] stopping me from joining but eventually they oblige me.

They will talk about the propaganda that was Biafra. When you look at the history, you knew and you heard, there was no way you wouldn’t support Biafra so I supported Biafra, which is why I really volunteered for the air force. I supported Biafra.

Venerable Professor Jacob Onyechi. Photo by Chika Oduah

It is not a question of supporting or not supporting. It got to a stage where they needed men for the armed forces. So, the law through the local administration was you have to provide. So, it is not a question of whether you supported or not. But those of us who were privileged, because that’s what I think happened, I was privileged to be able to volunteer for the air force because I saw the air force as a lesser evil, lesser danger to myself. So, that’s why I got into the air force. I was there till the war ended. The war ended ’70 [his voice trails off].

And I told my friends, there was this thing that I knew the war was ending but how did I know? In the air force after our training, they sent me to a place called Ihioma [a community in Imo State] where the air force headquarters was situated and the reason they sent me there was that they needed what they call the air force guards, those who did all the parade, military parade and so on. So, I was privileged after the training that I was selected as one of the air guards. And I stayed at Ihioma and when the war was ending, I commanded a quarter guard. I don’t know if you know the military terms. I commanded a quarter guard and in a quarter guard, anybody coming in, any high ranking officer coming into a base is saluted by that quarter guard. I knew important people were coming. I didn’t know it was the HDA, HDA, I mean [Chukwumeka] Ojukwu himself, General Ojukwu himself. So, I commanded the quarter guard that enabled him come into the air force quarter. That’s the Biafran air force headquarters. After a few minutes, somebody walked towards me, I looked, I saw he was a military officer, a rank of major and as a major, I needed to salute him. I saluted him but that man who came was my principal at Government College Secondary school Afikpo, Dr Akabuogu. He is now late. He came and said well done, son. That was a good quarter guard command you did ,but the story is that the war is over. We were on our way to Uli airport and he commanded Uli airport. He was accompanying His Excellency to the airport and he said to me, that was going to be the flight, the last flight out of Biafra and eh, he did that because he knew at Government College, I was into sports and he commended all I did as a junior at Government College. Eventually, they left and the next morning, we heard the surrender speech by Effiong and we all walked home from the headquarters.

It was a day to be happy about

As an air force man, I got promoted once. But, I was based at the major’s clerk. The BSM they call that. At Ihioma. The base sergeant major. He was in charge. The non-commission officer in charge of the base and he made me his clerk. So the duty was detail the guards, all those who went on duty. All those who kept guard at night. So, that was my- and I coupled that with what we call the air force guards. They create group that to national parades, national occasions and paraded when any important visitor came to Ihioma.

Count von Rosen, he flew what we call the Biafran Babies

Well, I will say the, I won’t call them victories because we were privileged to be near the people who brought the daily news. So, the radio house was there and we were privileged to be listening to what was coming in the waves about our successes and about our defeats. So we knew when Biafra was collapsing. We always knew because they send the air messages to the air force commander and so, the day we recaptured Owerri. That was for quite a short period of time. The forces against us, against Biafra were all over Owerri surrounded but they broke through and they recaptured Owerri but I think it didn’t last for more than a week or two because of their superior fire power, they came back and they recaptured Owerri. So, if you say any day, it was the day that they announced that Biafran forces have broken through enemy ranks to recapture Owerri. It was a day to be happy about.

Venerable Professor Jacob Onyechi. Photo by Chika Oduah

Well, I’ll tell you how celebrated because there was nothing to celebrate with. But, there was a supply line to soldiers including air force personnel and it was what we call kai kai now. You know what kai kai is. It is Gin. Gin. And what were we told? Please, supply this to the soldiers who were around and we supplied and there was nothing to celebrate with. Things were bare. There was scarcity of virtually everything food and all that. But, we gave them some drinks to celebrate the day in the air quarters.

…Biafran Babies, they were small planes

Yeah we had, we had mercenary support. We call them the Biafran Babies for Biafran’s angle. The Biafran, eh, I can’t remember his name Count von Rosen. The Head of State then, I don’t know how he did it, organized those people who volunteered. I heard they volunteered to come and fight on the side of Biafra and I heard the leader was Count von Rosen. He flew what we call the Biafran Babies. There were small planes that were always at Uli airport that took of from either Uli airport or Uga airport and all they do was take off, and in battle situations, they will strafe the soldiers on the ground. In fact, some of the times, they strafed both Biafran and Nigerian soldiers because my younger brother who was conscripted as I told you was strafed. You know, he was hit by bullets… So, that’s it.

I wouldn’t know, I wouldn’t know [the exact type of model the Biafran Babies planes were] but they were small, very portable [the planes we called Biafran Babies], that would land anywhere. In fact, if it flew within this campus, it could land on the road, on the express road, on the, eh, what we call express road and so we used that. We had eh, eh, eh, parking lots at Uga airport. They had at Uli. And so, they could take off and if the MiGs, the Nigerians used a very big MiG fighters, came after them, they could stop somewhere and hide until the danger to them was over and they could do whatever they want to do. So, they were small planes, very very small planes that could maneuver through difficult situations and do whatever the Biafrans wanted to do.

I think he’s [Count von Rosen] Swedish if my memory is right. He’s a Swedish and the important thing is that he volunteered to come and help Biafran out of the problems we were in when he was told the story of Biafra.

He came himself. He was one of them.

Well, if I say no I didn’t see him then that will be a lie because most of the times they came to air quarters and anybody who was entering air quarters, Ihioma then, I, because I was in charge of the guards. I know. So, they came. They came. Yes. I saw them. I saw them.

Uli airport became a nerve center

I was getting [information about the progress of the war] from the source because call them SITREPs then. Situation Reports. SITREP and they were always sent by their, I don’t know. They had a way of sending those things and the young man who was working and manning the radio was part of those that edited for this thing, I always ask him, what is the situation today? How good or how bad? And he’ll say. He’ll tell me briefly what it was. And so, I had an idea of when things were going wrong and when things were going right for us.

My elder brother was the one conscripted into the army. But, the younger ones were still at Ezinifite. They had moved from the church, the vicarage into town and they lived there and because there was communication between Ihioma and Ezinifite. The second Baf regiment, that’s what it is called. We call it the second Baf regiment. They were quartered at Ezinifite and so, I always find free ride any day I want to go back and I ran short of supplies. I always want to ask them to give me some or ask that somebody sent some supplies from Ezinifite to Ihioma to meet my needs.

Uli airport became a nerve center. If we survived for so long, the reason why we survived that long was because of Uli airport. Because relief materials came in. The World Council of Churches, all of them sent their relief through there. Uga was military airport. It wasn’t used but occasionally. But, Uli was what made us survive as long as we did because the relief supplies were sent into Biafra through Uli airport. Oh well, they say the, they say at times that the eh, supplies, military supplies came from, through Uli but what I know and what we were told in the air force headquarters is that the Uli airport is for supplies and Uga for military but we know that in between they used both of them for all sorts.

…because I was at air quarters and because I was a comman- I was a guard anytime any important person came to Uli, to sorry Ihioma, and he was going to Uli, we were given, we were told to go and safeguard them to Uli airport. So, I went as many times. In fact, not less than ten, fifteen times. We were always in the sentry. The guards that send people from Ihioma to Uli airport.

You know, terrible memories. At Ihioma, the World Council of Churches and Caritas had headquarters that’s where they supplied all the food and the milk and all that they needed. But, most of the time when they’re taking them out of Biafra, that’s towards the end of the war, they all left. In fact, I can say yeah most of them left from Uli airport. You saw them. We went around because we were in the air force commander’s company. We were his guards.

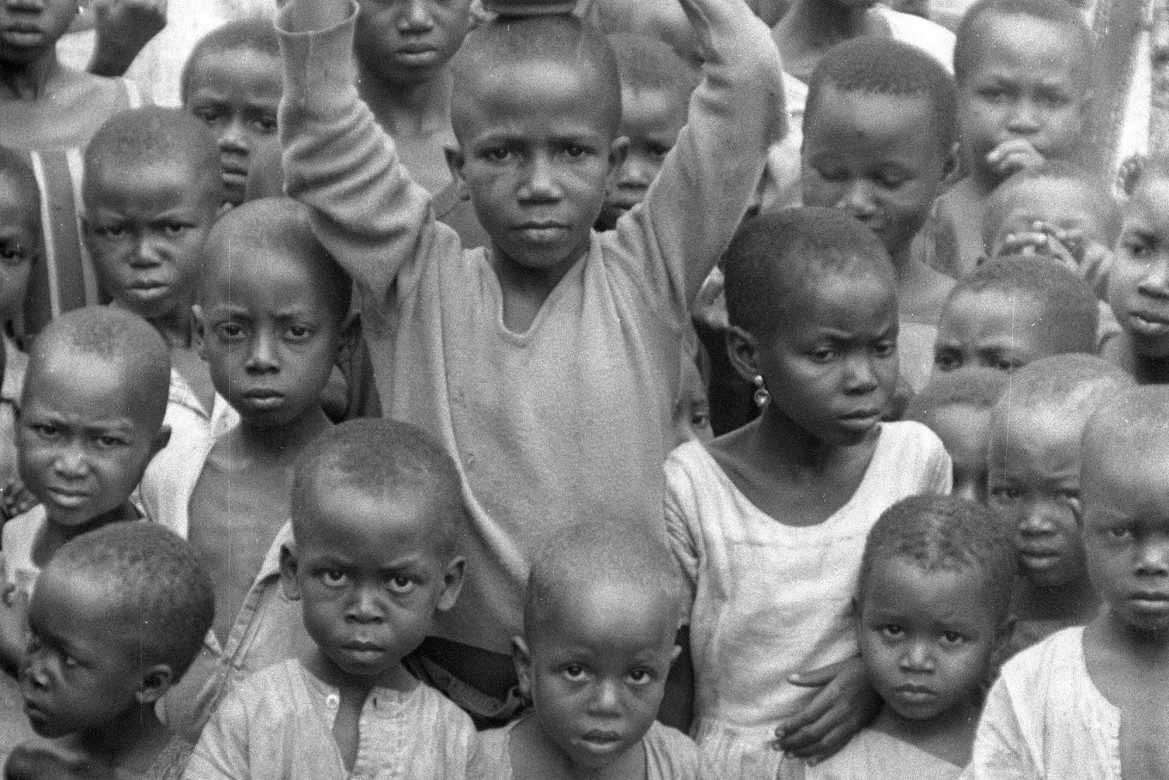

We went around with everything that was happening with him and we saw all these terrible, bad – even, they call them kwashiorkor kids! Kwashiorkor is the name. Terrible. Bloated tummies. Right? You know, if you look at their skin, whitish. Eh well, with heads as fat as that. Terrible sight for young people to see then.

I tell you why it didn’t affect me. Once the war was over, we were told to go back to Government College and we all prepared to go back to Government College. The Dr. Akabuogu, I told you was already going to be our principal. But, we didn’t go back to Afikpo. The reason we didn’t go back. The military, Nigerian military was occupying the college. So they used it as their, I think brigade headquarters and there was danger they would have left some unexploded armor. So, we didn’t go. So, we went to Enugu and stayed.

…he didn’t come back

We did [lament] as far as Biafra, I did as long as Biafra lasted. Well, the crying and the regrets, we were not in school. We had, we left school. We were at home. We are hoping to go back to school at the end of the war. We thought it will be a quick war and the war will be over. All the promises on both sides. And yes, it affected us yes but it was not indelible because after the war, we all went back to school. And the rehabilitation we had both from the Nigerian side and the Biafran side made us to get to back to the nick of our, that the peak of our developmental stage as youths. So we didn’t have any scar that made us [suffer mental trauma]. No.

I think there was [deaths of relatives], you know. I remember my cousin. He had just finished from school, school certificate leaver and he went to the military. I remember him. He was a sportsman like I was hoping to be which I became eventually. He went to war as an officer. He went to training and he didn’t come back. He died. He died. He died.

…we went to hide everything that would have incriminated Biafra

I was at Ihioma [when the war ended]. Remember I told you I commanded the last salute to the, to His Excellency and so once it was over, the surrender speech had been given, we walked the distance between Ihioma to Ezinifite. So, we all went back. We all went home. And eh, then, that’s it. I was at Ihioma.

Yeah, I commanded the quarter guard for His Excellency to go to Uli and catch the last flight out of Uli. That for me, when I remember that time, I say ah, that was a good thing I was opportuned to be part of that. I still remember where we went to hide everything that would have incriminated Biafra. There was a little town where I call Ogbaeruru [a community in Imo State]. So, in those last two days, I didn’t know! We were told to go and dig up and bury the secrets, all the photographs of the Biafran Babies, all those things that would have, if they fell into Nigerian hands, incriminated Biafra. We went to a gully side. They call the town Ogbaeruru. I still remember and we- Ogbaeruru, a town where we dug up and buried all those things that would have incriminated Biafra.

Photographs and then secrets, documents. Yes. Documents, eh. The reason I remember it so vividly is that on the way to that place, if it were not for providence, I would have been a goner. I tell you, we were carrying all those things in a tipper and we were on top with all the guards and so on and the driver of the truck didn’t gauge right. Just as he going under a tree, he shouted and we all ducked. We thought it was an air raid or something. We all ducked and the next is that we heard this hard bang. The structure of the vehicle hit the tree and if we were still standing upright, a lot of us should have gone down, dead, because it was the head that could have collided with whatever. But eventually, we survived it and I, we, would not stop giving God thanks for that day. Whatever it is that happened, he saved us. That’s the way I look at it. He saved us. On the last day of the war? No, it would have been terrible.

Well, well, it’s how many years now? Fifty years. If there a landslide, because that’s a gully sight. I wouldn’t be sure that the documents will be there because what would have happened to them, is what I don’t know. I don’t know.

…we had nothing to defend ourselves

Well, what I’ll say is that the memories are dim now but not too dim. This happened after the war. We had just gotten back to my own village. I’m from Abatete in Anambra State, and a lot of people were trooping to a scene that is recorded in so many stories about the war. The debacle when the Biafran forces waylaid the Nigerian forces. I heard what happened was that they had reinforcement whether from Benin, or from wherever and they were going to deal, that was the final push for the war and some Biafran whether, I wonder ingenuity that’s what I’ll call it but I know it does happen. They say he triggered his mortar and it fell on a tanker carrying fuel and ammunition and you had about two, three miles of destruction of ammunition that would have been used against Biafra. So, seeing that long array of destruction, occasioned by that mortar dropping on one of the, whether it was the tanker carrying fuel or carrying an armor or explosion and the whole range of destruction met a lot of, you know, it still sticks because that’s what should have been used against us in Biafra. So, the, it’s eh, I’ll put it as God’s work because at a point in time, we had nothing to defend ourselves. The armor had gone low and for that to have happened, they call it the Abagana sector. You would have read about it, or you’ll see it somewhere. The, it was an ambush that decimated a lot of armor.

I wasn’t there but I went to see after the war. We had come back to my village and it was still fresh and people were still going. I said, ah, I want to see what the story line was and it was true. It was true.

Venerable Professor Jacob Onyechi. Photo by Chika Oduah

My cousin. He just went to school of infantry on the Biafran side, qualified as an officer and went to war and didn’t come back. Very close.

My brother survived. I tell you about the other story about the survival. I came back home first. I knew the war was ending. So, I took off immediately after the surrender document, the speech.

…the joy of it made her faint

So, I walked home. My mom was in her farm, yes, doing the normal thing women do and she saw me and she was so happy. Thanking God and then, the time of waiting for my brother, my elder brother who was in the Biafran army. You know, I was in the house veranda, it was an upstair [sic] that we were living in, in town and I was looking out. My mother was in the same farm where I saw her when I came back. And all of a sudden, I saw my mummy go down. I saw my mommy go down. I had to rush down hurriedly to see and note what was happening. I didn’t know she had seen my brother walking back to the house.

[Laughs]

I don’t know whether he had his shirt on but, if you know what travelers in terms of soldiers or, my mother had seen my brother walking home and the joy of it all made her faint and we had to go and revive her and when she got up, she was so happy. And we asked why did it happen. She was pointing to my brother. You know, we live in a place where you’ve to walk up to a hundred, a hundred and fifty yards to the house. So, she was in the farm and saw my brother walking home and the joy that he, too, survived made her go down. So, we thank God. It’s what we tell our stories now. My mom is late now. She’s gone to be with the Lord and when we meet, when we see, we’ll recall these things but my sisters all survived and I had five of them.

And the way of survival was that they were helping mummy make- you might have heard about some soap. We call it ncha nkota, very medicinal soap that we make from palm whatever. That was what she did and she will do her daily ration and they’ll walk, was that about five miles to Igboukwu [a town in Anambra State]? We call it Nkwo Igbo to Igboukwu to sell.

…and the 20 pounds we were given

And that was what kept us, and she earned some money, very good money, selling ncha nkota that people bought and made up for what the old man got as his retirement benefit from his pastoral work. So, that was it. They went to Igboukwu, sold them and my sisters, walked the five miles back and that kept them until we came back and the war was over. And so people were now to go back to what they were doing. I went back to school with my brother. Fortunately, we were in the same school, Government College Afikpo and the 20 pounds we were given. Everybody would have heard about the 20 pounds. Everybody in Biafra, whether you owned a million dollars, a million pounds, a million naira, you were given 20 thousand naira- 20 pounds.

…If you had money in the bank, you went, to, I collected 20 but out of the 20 some people gave us some money and so we had some money in our pocket to go back to school. We thank God for all that now.

Because I was in the air force, I was sheltered. I didn’t go to the Biafran army. And because I was at the air quarters, I was privileged. All I heard was the news of how we were doing well and all that and because of the position, because we were always in the air force commander’s guard, looking after all the high ranking officers. We, I was sheltered. No doubt about that.

[My brother] the Biafran Babies hit them. He still carries that wound now. I told you about the Biafran Babies. They were in the war front, right, trying to engage in military, and the planes came to destroy the military but they missed their mark and hit both Biafrans and Nigerians. Yeah, so, that’s the, that’s the…collateral damages they call it these days in the military. Yes.

I remember I collapsed….

If I tell you I didn’t hear about that that [soldiers raping women] would be very very wrong. Even after the war, it persisted. You ask me how? Once the war ended, we went back to Government College we were at Enugu. I was a sportsman. I played cricket. I played hockey. I played football and we had our friends, camps, right? They were young ladies. We were boys, young boys. Boys’ camp. The men were in their own camp and there were girls who were in the camp too, to play, it was for them, hockey, they didn’t play cricket, it was hockey. And the military men were making advances. For us, what we said, if they come to you and you agreeable that’s your business. We’re not going to. I am talking about when we came back to Nigeria now, when we were assimilated back into Nigeria. But, you daren’t in those days during the war. It was part of their war whatever. If they overran a place, anyone they caught, they did whatever they like but, that’s because I wasn’t privy. I didn’t know about of it. I am talking about when we came back as students, as sportsmen, they still continued their amorous desires but it was for the girls to agree or not agree. If you didn’t agree, they didn’t touch you. But as war booty, once they overran a place, and then, I must say, I must say, it wasn’t all, you know, by force. Some of our women went to them because they needed what they had. They had the money. They were in control of those areas. And we call it attack. Afia attack. Ok, you’ve heard that? So, they went behind enemy lines and if you go behind enemy lines, there were prices to pay and so, I am not too clear about that one. So, I won’t delve into that but that’s what happened in Biafra.

…some of them sold themselves…

They’ll go behind enemy lines, go and buy those very essential commodities needed and come back to sell them to Biafrans and it didn’t go without a price. So some of them sold themselves and it’s what you don’t have to talk about your people. So, yes.

Venerable Professor Jacob Onyechi. Photo by Chika Oduah

When I joined the air force, [as part of the training], they took us to a base, the air force training base. It was located at Ikenazizi [a community in Imo State], a place we call Obowo. It was there we did a short training. It was both the military and how to work your rifles and all that… and after that, we all dispatched to different fronts. I was lucky because they came recruiting tall, strong looking, young boys and we fell out-we fell in line and they counted the talks ones and that’s how they made us air force guards and the others, they sent either to one Baf regiment at Oguta [a town in Imo State]or to two Baf regiment, our fighting forces in the Biafran air force then.

I was sick or malnourished

Two Biafran Air Force. Two Baf regiment. I’m talking about regiment. That’s what you call them then. One Biafran Air Force regiment at Oguta. Then, two Biafran Air Force regiment at Uga. So, they selected us as the people who did they parade. I remember I collapsed some one of those times, we were doing the national day parade. I don’t know what happened. I think I was sick or malnourished or something. I collapsed and I was sent out. I was carried but eventually I got back before the parade ended.

*Venerable Professor Jacob Ukwuchukwu Onyechi granted this interview to Chika Oduah from Enugu State, Nigeria*