My name is Nduka Agbim, a resident of Georgia in the US.

I was born 1951, December twenty-first. So the war is called Nigeria Biafra War of 1967 to 1970. Of course, by ’67 I was in high school in Stella Maris, Port Harcourt.

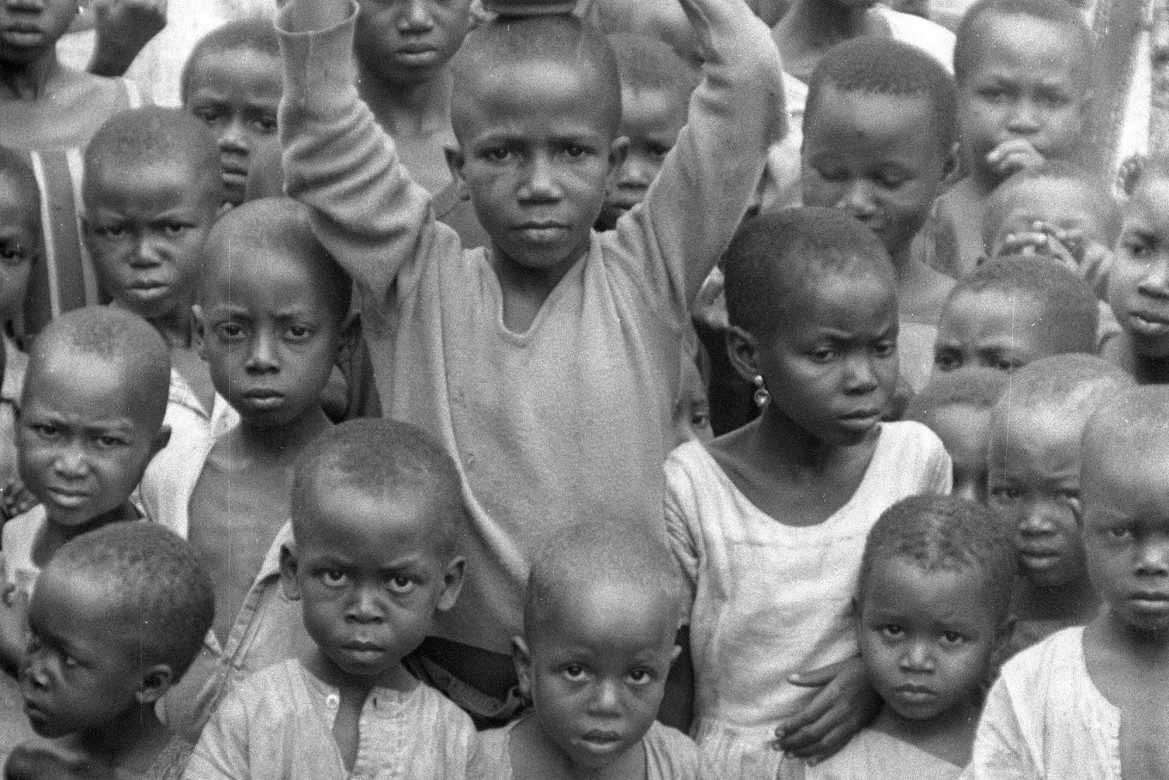

Nduka Agbim remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

I was in what they called Class Three. It was a Catholic school, Stella Maris. Minister of the Sea. Well, the war began actually when I was in school. [Chukwuemeka] Ojukwu came to address us at the school, Stella Maris.

It’s a boarding school. A Catholic boarding school. Under the Port Harcourt archdiocese and under the principalship of Father Sleven, Father T. B. Sleven and Bishop [Godfrey] Okoye was the bishop of Port Harcourt at the time and Ojukwu came to address us, telling us about what was going on in Nigeria and actually at that time his main target was the people in high school and upper– no, lower six and upper six. Those who have gone beyond the five years of secondary school.

He addressed us in a general school assembly which we normally have every morning before classes begin. He was telling us what was going on in Nigeria, how the Biafrans, how the Igbos have been oppressed for many years and how it has escalated to where we just have to not keep quiet anymore. That we have to fight back, you know. And then he was telling us to really think of how much longer we’re ready to condone that type of mistreatment. In 1950 a bunch of people got killed in Kano, before independence and since independence, people have been massacred in the North under the leadership of the northerners. Don’t forget Tafawa Balewa was the prime minister at the time. People have been massacred: Christians, mostly.

I guess the whole idea was to bring everybody to the Muslim world. But because at that time, the South was predominantly Christian. That’s what we were at the time. Ojukwu was not coercing us into war but at least telling us the benefit of fighting for our rights, you see. And to the point that the eastern part of Nigeria needed to secede from Nigeria itself, you see. So. I’ve forgotten the exact date.

[He came and spoke to us way before the war was started.] It was just at the time, it was before the war was declared. Ojukwu was going from place to place talking to people about what was happening in Nigeria and the necessity for us as a group to fight.

[I felt there were] too many uncertain things when you hear something like that, your imagination goes wild. How is this going to happen? What’s the impact? Because we’ve never been in a war before.

Yeah, we lived in Port Harcourt and in Class Three we didn’t see that [the oppression of Igbos]. But oppressed in Nigeria, yes, based on what Ojukwu was saying.

I had a cousin who in 19- well, that was right after the war – right at the time the war was about to be declared. He was an engineer, just came back from London – PhD electrical engineering- and was working in a place called VON [Voice of Nigeria] in Jos and he was massacred by the Northerners with an axe. You see because at that time things were not good, that right in Nigeria and people were beginning to head south but he refused to go.

…they got an axe and cut him into two

He stayed. He was the head of the department that he couldn’t just leave and all. And we kept telling him, “Say look, you just came back London. Forget that place. Leave.” He didn’t listen and in the middle of the night, they got an axe and cut him into two.

Nduka Agbim. Photo by Chika Oduah

That was it. See?

And that was ’66. And ’67 of course the war was declared. That was the beginning of the catastrophe of running up and down and other stuff. So from Port Harcourt, with that declaration- in fact after Ojukwu’s speech and everything, he started advising people to head to your hometown.

He [Ojukwu] made people worry. He made people also want to say, “Yeah, we want our independence.” But we didn’t know to- but we had a history teacher at that time, Mr. Odu was his name, and I remember in his West African history class he was telling us, even before Ojukwu came to the school, if you want peace, prepare for war. He actually interpreted it in Latin… We didn’t understand the whole ramifications of, or implications of that statement until the actual war started and everybody was like, started carrying things on our head, walking.

I walked 40 miles on my foot from a place to Orlu headed somewhere unknown at the time.

We had to leave [school] because by 1967, as soon as the war was declared, the principal made an announcement that everybody was dismissed. We had to go. The principal who was Irish, I don’t know if he stayed or he went back immediately. Because we had a bunch of white people. That school was predominately white. Dynamics changed after Ojukwu came and those people left and they appointed a man from Owerri to be our principal at the time.

Resistant to change, the students did not appreciate his presence in the school because he was there giving us bad food and other stuff. All the good things that the white people used to give us were gone. The war was declared. We all had to leave Port Harcourt and started heading to the hometown and with my only brother who lived in Port Harcourt then. The parents were living in the village and I was in Stella Maris going to school… so we left and as we came back to the hometown, that’s when the whole catastrophe started.

Nduka Agbim. Photo by Chika Oduah

We were also conscripted into the army

So initially they were recruiting people who were older than me. Don’t forget we were Class Three which you call, which is like a junior in high school here [in the United States]. As opposed to people who had already graduated from high school and they were like first or second year in college. They started with those kinds of people until they ran out of people then they came to our side. But my role, one of the roles I played at that time with my brother, we were supplying motor parts to the army at the time because there was scarcity of things and we were going to buy these things from the junk yard and then selling it to them so they can use it to repair and maintain their vehicles. There came a time when we were also conscripted into the army. I now said, “Oh!” [laughs], you know.

My uncle who was a medical doctor at the time was a respiratory radiologist. So he said, “No, no, no.” He won’t allow me to stay in the army. That I have to come out from that place” and all that stuff. So they took me to 11 Division.

[I was conscripted when] I was asked to go and get something from the market by my older brother. So on my way somebody said, “Don’t go any further, they are conscripting people.” I said, “No, no problem.”

Then before you know it, it was me.

So because I was known kind of in that environment, so some people that knew me and saw me when this thing happened went and told my brother. My brother told my uncle, who was the radiologist, who had also joined the army. He turned around to the army officers that he knew and said, no no he has to come out. Later and other stuff saying that I’m not fit to be in the army but the people said I have to stay. Yeah, but then I did, not for long because it didn’t get to where I would go fighting. But I was with them, I was with the 11 Division with the general army under Colonel [Timothy] Onwuatuegwu at the time.

All those colonels were coming to our house [Major Joseph] Achuzie, [Major Chukwuma] Nzeogwu, all those people, they were coming to our house…that was before the [1966] coup.

We had all those army colonels, Achuzie, this guy, Onwuatuegwu, all those colonels, remembering their names.

I know a bunch of them but then we were supplying– there’s a place in the army called S&T, supply and transport. That’s where were supplying these military parts for them to use to repair the vehicles. So that introduced me to a bunch of army officers and all. So they all knew me.

So when this thing happened, and my uncle told one of them and they came to the place and saw me, they said, “Come, you’re not staying here.” So, I came out. That’s how I left. It was a very terrible experience. But then we were running from place to place before that incident, my family were staying in another town. And we were depending on the Red Cross for food and all that stuff because we carried our stuff and moved to another town.

I’m telling you, it was bad

Me and my brothers and my mother and we just moved. My other brother was staying with one of my other older brothers and then my sister, my oldest sister was staying with other brother. So three of us together were still with my mother by the time this thing happened. So were running from Nimo anyways.

Nimo is between Abagana and Enugu. Yeah, that’s where we were. And we moved from there to a town called Abacha.

I’m from Abacha to Eziowelle my mother was from Eziowelle. We transitioned into that place and it was after that Eziowelle place that I went to my brother to Orlu where I got into the army. Sorry, I’ve been going back and forth.

[laughs]

Just remembering things. So that’s how this whole thing happened and then we were there for ’67 to ’70. Involved with the army intensively and even towards the end of the war, we were- I was with the army then. I didn’t know the war had ended. Yeah. And people were saying, “The war had ended. The war has ended.”

I remember my motorcycle then that I was driving and I was driving the motorcycle and somebody said, “You need to go and park it. The army will take it from you because the war has ended and they are looking transportation to” [voice trails off]. You know?

The war ended and people suffered and suffered and suffered.

Nduka Agbim. Photo by Chika Oduah

Otherwise I would have been the victim

The Red Cross, all those relief agencies were there supplying food and medicine and everything to the people. It was a terrible terrible- I mean I could remember in one of the houses where we were in Abacha. We were sitting just like we’re sitting here and a ferret, the army vehicle, was coming from the town close to my mother’s place and they were shooting and then we were there listening and this thing pierced through the roof and go whirrrrrr on the ground. Very hot and red. Then I just did like that and it stopped somewhere. Otherwise I would have been the victim.

You see, a lot of shooting going on, you see, and they were just releasing bomb shells and all kinds of canon and everything.

Oh, I was there [in the army] for at least, man, hmph! Okay, I was there for at least six months? Yeah.

[Sings]

Enyi oh, enyi oh [Comrade oh, comrade oh]

Enyi Biafra ala go [Biafran comrade is gone]

Cheta Chukwuma Nzeogwu [Remember Chukwuma Nzeogwu]

Chukwuma Nzeogwu bu enyi Biafra [Chukwuma Nzeogwu is a Biafran comrade]

Enyi oh, enyi oh [Comrade oh, comrade oh]

Enyi Biafra ala [Biafran comrade is gone]

Enyi Biafra ala [Biafran comrade is gone]

At that time there were several, several, several songs about the war.

Coconut was our very first favorite snack or food or something [in the army]. Man, these people will cook, give you food, watery type of food. You talking about good food? It was not. Even the civilians who never joined the army but were getting relief from Red Cross and everything had better food than those of us who were in the Army. Because we were there starving. I’m telling you, it was bad.

People were just fighting hungry

I thank God for that [never getting sick] because it was so bad that after a while the Biafran soldiers started going into the farm uprooting people’s produce and then forming their own thing, making fire trying to cook. Because we didn’t have anything. No food. People were just fighting hungry.

Nduka Agbim. Photo by Chika Oduah

I saw him [Ojukwu] again because Colonel Onwuatuegwu was one of his top lieutenants at the time and I think he was- I went to 11 Division at that time to deliver something, to deliver the motor parts and Ojukwu happened to be around, with all sorts of security you can imagine was there. That’s when I really saw him again. At the time he came to address in school he wasn’t really fully militarily dressed and all that kind of stuff because Biafra didn’t have uniform then. You see? But when I saw him then he had a uniform with the Biafran sign all stuff on it, the army camouflage flag tailored after the American military uniform. That’s when I saw him that time.

If it were today’s world, I would have taken a picture of him.

[laughs]

My mother was alive after the war. She survived and she just died 2012. My father had been dead a long time ago before the war. I didn’t even, I was growing up when he died.