My name is Elder Macpat Chike Emerike.

I was born 1950. The twenty-first, August. I was born at Amaokwe Item [in Abia State]. Yes, I witnessed it. I witnessed it all the way because that time I was, my dad was still alive and we were living at Umuahia.

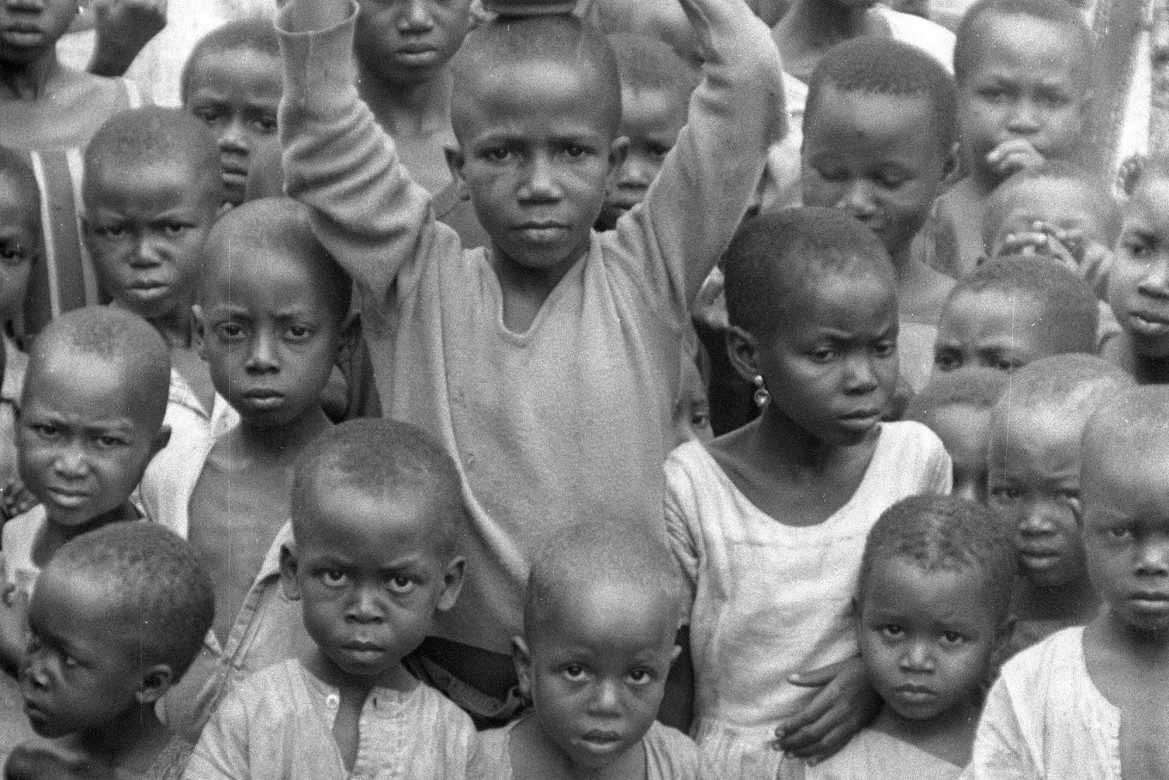

Macpat Chike Emerike remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

Nobody could even believe it. It was just on a Friday like this. We started hearing gunshots and everybody, rockets flying in. Everybody was now- my dad was a police officer. He read – and he went to – and they were now told to move straight to Orlu, where they will now get the next information as to where they will be positioned.

Then we now moved. We had to trek from Umuahia to Orlu. It was a two days journey.

[My reaction to the first coup of January 1966] really, it was just what one cannot just define. Eh. I heard it because we have our radio and TV. All these things, we were just seeing them on TV and hearing them on news.

We had a television that time and also a radio set. There was a type of powerful radio- my dad came back from US, from London that time- you can always get connected to BBC. We were getting information all the way from BBC. And the one we now hear in Nigeria, we now combine it to make a difference, to see the truth. But along the line, it’s an undefined clause. It’s an undefined clause. So we now base it on what we now can see and what we now get from the soldiers who go to the front and come back.

I was a student [when the war started].

You are still suppressing them, killing them…

What happened- since I wanted to actually to go deep. I now discovered that these were people that were fighting for their own rights. And, well, I hope- it’s not bad for a child to tell his father “I want to go and stay on my own,” but the Biafran or the Nigerian government that night took it either as an insult, that why should these people be distraught? They said they want to stay on their own. They are not allowing them to stay on their own. You are still suppressing them, killing them, and the type of deaths, massacre that happened, where a woman was cut. We saw it on the TV. All these things we were seeing on the TV.

Inasmuch as I can’t remember [the exact day the soldiers came to Umuahia] but they came through Port Harcourt. They came through Port Harcourt, then they now entered into Aba or thereabout. They started pushing. It was just a free ride for them. They were now bombarding. The first thing that came into Umuahia was the jets. They would be now shooting guns, wah, wah, wah and the people now said, “Enh?! So this is real.”

So everybody now started taking shelter. We were now pushing. Nobody knows. Everybody was just pushing. If you see your fellow human being, moving this side, you move this side. If you see them moving left, you move left, right, forward…. It is better seen more than described.

Macpat Chike Emerike. Photo by Chika Oduah

I was just in the house when I said I could not believe it, so I went looking for my dad to come back from work. When my dad now came back from work, he told us that we were now moving. That the place, that the DPO had told them that they should shift and start coming down to Umuahia. But there were no vehicles. My dad had a bicycle. So he had to carry some load that he was able to carry on the bike, and now carry the other one- our bed, a wooden bed, on the head. We were now moving. We were moving until we now came down to Orlu.

[Jets were] the first thing that came in. They were so low. There was no firing. That was just the thing that started telling people that something have go- some of them were like this and some of them were like this. They were just displaying their, this thing.

Immediately my dad came and gave that information, because I know they also had a signal in the office that tell them to move. As we are moving these things were just dropping. And when they were dropping we were now told to lie down, but it’s a pity that some of them who wanted to see the jet, really, just stood down like this, by then some of them were just cut up. Their heads were just chopped off immediately.

…she now threw away both her goat, her children…

Yes, yes, yes, I saw some of these things. There was a woman that was carrying both her load, with her goat, and their little baby, and then once she carried a baby on her back. Immediately that jet now dropped that bomb, she now threw away both her goat, her children, everything. She was now running alone. Where she was running, nobody knows, but we were heading to Orlu.

We were trekking. There was no vehicle. Even, when we came to the police station at Umuahia, what do they call this- 7 Guinea at Umuahia. Very close to Mbakwe’s house. We went to the police station and there were vehicles seized but there was no fuel. Then the police officer now issued a statement that anybody who can drive, you can move with the vehicle. But there was no fuel. People who moved were now- the children will enter into the vehicle, then you will be pushing. When you now come to a hill, everyone will now enter and the thing will now push you up. Then you continue pushing.

My father was just pushing the bike because of the load and I was following him at the back.

By that time my mother and brothers and sisters were on the other side. They were in Nigerian side. We were cut off because I was living with my dad that time.

Really what happened, and when the war was too much, already that massacre that started, all of them came back from Lagos. Then they now went to the village and stayed. It was that because my dad was a civil servant, by that time he had not retired from the police. He was still working in the place and I was now living with him. Some of them were on the other side. It was now after they said the war has ended. Even as we were coming back, nobody could believe it until when now came and saw our mommy. I saw my mommy and younger ones but what I saw on the road is better seen than described.

…dead bodies lying carelessly everywhere

You will see human being on the road, just lying down, maggot coming up and down on them. It was just a shame. And by that time we were living very far. We went and saw them. I had depreciated to this size.

Macpat Chike Emerike. Photo by Chika Oduah

That is, the dead bodies lying were everywhere and that was my first time of seeing dead bodies lying carelessly everywhere. Everywhere was, everywhere, and when were about coming out, the soldiers, Nigerian soldiers had fully entered into Umuahia and to Orlu that time. Then what they now gave us was sardine and bread to cool our, this thing.

The 1966 [massacre]. All of us. Well, I was born there and all of us were now taken. That’s when my dad dey at the police headquarters force. CID Force at Lagos. That was where he was as at then.

Immediately that massacre happened, seeing how things were moving, it was just not that defined, so in order to secure his family, all of us now came down to village. All of us, that is my mother and my younger ones. It was I and my father that were now living in town at Umuahia.

My mother went to the village she was married at Amaokwe Item, Amogba.

My siblings, the first daughter was staying with her proposed spouse, but, the person that intended marrying her was the one that took my senior sister to go and stay. He was a captain in the army, the Nigerian Biafran army, then he now took my senior sister.

Then all other ones were now in the village with my mother. The young ones, some of them were ten, some of them were five, some of them were nine. All of them now decided to leave town and now rejoin after the war, when we were sure the war had actually ended. We now boarded a bus. That bus, I don’t know how we were. I can’t just, yes. I think we boarded a long, a very big trailer that took us down to our grave.

We now saw our momma. It was another reunion.

[It was] around that ’68. ’68 or ’67 but I can’t just remember the year. I can’t just remember the year [Nigerian soldiers came to Umuahia].

Umuahia was the last place [to fall to Nigeria], then they were now even. It didn’t come to Orlu. Eh? All those places, but at a point, they now, they now gain access through Owerri, Port Harcourt, Owerri, and rushed in there, and immediately Abagana fell. Abagana sector which was the horrible area, or the stronghold of the Biafrans and all the rest. Things now went.

Really, what happened, my dad was still with the Nigerian government, and after the war, the Nigerian government, police said that he was in the side of the Biafran, he said no, that he was still on duty when he was now told to come to the first CID at that should be, Umuahia. So how can he fight the war? He was still operating with the Nigerian government files and the rest. He was still under them, but at a point now they wanted to dismiss him. He said that they can’t dismiss him. He was on duty. Then, when they now dismissed him, he now filed a case and he was able to win that case in the law court, then they now retired him.

He wasn’t in support [of Biafra]. Everybody was even embarrassed of him, till today. Everybody was embarrassed. Mostly my dad was embarrassed. After having put in, he joined the Nigerian police far back as 1948, 1941 and he was expecting that he could have retired honorably but the war just scattered, and that was why he died earlier, because if not so my dad couldn’t have died at the age of 53, after the war. He died ’81, so if the government of the day, the Nigerian government could have compensated him, knowing fully well that he was working with Nigerian government during the war.

[His relationship with neighbors here in Umuahia], it was just cordial. There was nothing. It was- you know, you know the- we take it that the Nigerian police, eh? They were just free. They were just as a neutral, they were just standing on a neutral ground, so for somebody to have start taking politics, that’s an individual set up. But himself, he was just free.

Really what happened, I believe I do know that when you are 18 years, you are free to live on your own. You are now an adult. You are free to live on your own. I don’t see anything wrong for one to say, “I want to be alone”.

I am just giving an example. They have the right, the right to say I want to be alone. I don’t want to stay again with daddy, mommy, at this my age, so let me detach myself. And I should think.

I am not a Biafran supporter. I am not supporting anybody.

At that time, I was just a novice. I was just watching for the sake of watching. And even, there was a book, because I wanted to know more, the details, some books they were writing a lot of books and I was able to pick one. I lay hands on one. Because when I was in school I was also a journalist. Eh. So I picked up- they said that because I was involved with – it was written by Odimegwu Ojukwu.

If you die, nobody cares

[Going back to that trek from Umuahia to Orlu], it was horrible. It was horrible. As young as I am to be trekking. And it’s just like from here to Owerri. We were trekking on foot, inasmuch as we were many, we were trekking. Even at a point we now came into seven- I don’t know what they call that seven place. At Umuahia, we had to rest, and if you see the type of water- because everybody was so thirsty. If you see the type of water, greenish, we were just taking the thing.

Macpat Chike Emerike. Photo by Chika Oduah

Yes, the water, a pond, like this. A pond. That is, ehm, potholes. We saw water there, because we were thirsty, we didn’t even mind whether we had gone to die the next time, we now started taking it, and that was what sustained us until we now got down to Orlu. Ehen. It was then after the Orlu, we now started coming back to Owerri.

It’s, em, from here? Almost the whole day. Because we took off in the evening, expecting that if we get down to the police station they would give us a vehicle to pack all of us down straight. It was a two day journey, two day journey. Two day journey. Hectic. There was no food. Everybody was just, any place you get down, you land, that is your home. If you die, nobody cares. We were just working on faith. That was just what made us to leave that Orlu.

Em, you’ll see, everybody just felt as if it [the war] was going to end overnight. But we continued seeing more, eh, the Biafran side, making announcements that they are advancing, that they have now reached Orlu, that they have now reached the Niger bridge. They have crossed the Niger bridge. They are now at Delta at Sapele. Everybody was happy that the Biafrans were advancing.

[Before the soldiers came] we were just living a normal life. It was just on a bright day, around 4 or 3:30 we now started seeing craft, gba, gba, gba, gba, gba, gba, gba, gba, gba, gba, gba, gba.

Phew! Phew!

That was the bomb you’ll just be hearing from the craft and thank God that we survived it. I and my family survived it.

It was after the war that I now continued with my education. I was in JS1 [when the war started]. My last day of school, that should be third term at Oboro Grammar School, around ’60s. Around ’66 or ’65. Ehen.

It should be. It should, yeah around that time. Immediately the war now started, when there was an uproar, we now discontinued it.

Really, what happened, there was, the only thing, the information we got from the TV and from the BBC because the BBC, anytime we tune the BBC, we hear information about the war, and that was just the only place we were relying.

[It was after the declaration of Biafra] that I stopped going to school. They [the teachers] said we should go home, that we would come back.

That day, inasmuch as it was not all that free because everybody now came, groups of students gathering and the teachers also gathering and we also go together asking how is the situation.

They’d give us their own version and it was just, they were just based on that oral, but it was just more of assumption. People were now saying whatever they know or whatever they have heard.

Eh, it was just interesting. It was just- I felt that the war couldn’t have extended to that, it was just an, that is a month’s war, then everybody would now come to normalcy, but since it dwelled to that point now.

I am a boarder. I was living in the boarding house at that time. So there was no much stress in terms of my education.

I went to class and had my normal studies, but along the line, the teacher also engaged in some little discussions about the war. They said it may continue. Yeah, some people say no we don’t want it to continue. Let it just end because it was affecting our education, per se. So that was it.

I was doing all the science subjects. Physics, Mathematics, English, Chemistry. That was where I had the interest. Because, really, what happened- I started- what happened here- if you get down to SS3, SS2, you will now be picking, these people should go science. But I didn’t express that. I started from the day I entered into first class, my first class in secondary school, I started, with the sciences.

It was the principal [who told us to go home]. I was just in JSS1. Everybody was just say, ah, has the war gotten to this? It should be around 10 early morning assignment.

The principal came and informed the dean who now assembled us in the school hall and told us, gave us the information and then everybody now started leaving the hall…that we should not stay in the school more than this time and nobody should sleep in the dormitory because I was living in the dormitory at that time.

Then I now went to dormitory and from there we started leaving. [I collected all of my belongings.] I didn’t leave a dime in school because I was not sure when we’ll be back.

I told them [my parents] the situation. I told them that, they asked me what happened. They said that the war have started. I asked them “which war”? They said Nigerian- Biafran war. Then we heard that, even my people ran inside the bush and they were staying all through that Biafran, as they told us because they narrated the story. All of them were in the bush, not ordinary bush. Forest. Because in that [area] we have a forest, a forest that has stayed more than hundred years. They were now camped inside it.

My mother was also in the village.

From there, they, I didn’t enter the forest but they were there already. They left Lagos to the village, direct, where we now felt that security is safe for them. Then those of us that were here now, I and my father, we now said anytime we can just, but even at that, to my greatest surprise, one day, the, the, the, the Nigerian soldiers, yes, came from the other side, because there’s a division. Biafra. Nigeria. The Nigerians came and said that I’ll be going to the war, one early morning, I went to fetch water. I started shedding tears. They said this is not [time for] shedding tears.

Then I now said let me go and drop my pail, that I will follow them. I now tapped at the door. My dad now opened and my dad was a police officer then, and he now met them at the camp where they were conscripting human beings, conscripting everybody. He told them this is his son. The commander that was in charge now said, “No, this is not the type of people we want.” That was how I freed myself.

I have never seen corpse, but that day…

They [Nigerian soldiers] were now conscripting people, putting them in the forefront. Because there was a demarcation, there was a bar, which Nigerian soldiers now stopped, the war ended. Then there was just a portion. But at a point, the whole thing- both the Biafran soldiers, were now destroyed. The whole country was now the Biafran soldiers.

That’s when Nigerian soldiers now took up the whole country, the whole country at that time.

My worst was, because I have never seen corpse, but that day… immediately, I saw corpse. One, two. All of them were just decaying, decomposing. One. Two. Three. Four.

From here to the tag, you will see up to fifty men. You’ll see skull. Oh, God have mercy. God have mercy. God have mercy.

So the thing now affected my health. I now dropped.

It is just better seen than described. It is just better seen than described.

Macpat Chike Emerike. Photo by Chika Oduah

I also miss some of my relations, but God knows the best. God knows the best.

From Orlu- from Umuahia to Orlu, two days. No food, except that place we came and saw pothole and tap water. There was no food because it was just I and my father. I was carrying that bamboo bed that stretches from here to here. I was carrying it alone on my head, then my dad was pushing a bike with his one-loader attached to it.

[From Orlu we went to Owerri and that’s where we stayed until the end of the war.]

We just came in, we packed in, we just saw one of our relations. Her building. It was empty. Then we now packed in there. They were now going from Orlu, from Owerri, to Mbaise to collect relief because there was this Christian organization, this Caritas.

There was a Catholic school, a Catholic church there which one of our family friend Monsignor Ogbonna was heading, so I normally trek sometimes I would board a vehicle that would drop me at Mbaise that now enter to Owerri, to Obowo, to go and collect relief. It was just those relief, that, what do they call it, em, I have forgotten the names of all these things. What they call that food oh, they give to us?And some other little things. We were just managing.

Sometimes, my dad would go to work, they also give him some of the relief. But what happened, on our own side, we were very lucky, because there was one of my relation who was also in London, who sends, I don’t know how, whether some people get it to here. That was how we were now refreshing ourselves.

Daddy, what are we going to do?

[We received the packages from London] through one of our relations which, eh, we don’t know how the thing went through, but the thing really landed in our house, so we were now feeding from there. Then he now, there were rows of tobacco…lux [soap]…and the food. So we were now feeding there, even self, at a point, I now told my dad even if this world can continue from the next five years, we will not feel it because of the relief we are getting from outside.

So that’s it.

Any time the one we have in the house gets exhausted, I will tell my dad that I will go [to Mbaise to get more relief materials]. I will move with vehicle on coming back. Then, now the worst day I also experienced was the day I trekked from Obowu to Owerri. I came out Obowu and now moved Mbaise, which is more than, it’s just like trekking from here to Onitsha, in the night. I was just on the main road, on the main road, walking alone. I was with my little Bible- this pocket Bible, I will just putting it on my hand and that was what saved me.

So this [Bible] was what I was holding that time. This is what gave me strength and faith and also my father also developed his own faith, because anytime there is no food I ask him, “Daddy, what are we going to do?”

He’d say, “God will provide.”

Before I know it, there will be a knock on the door. My uncle, who is oversee, will now give us, bring us the relief. And we were very happy. Even the tobacco…we were selling the tobacco and we were getting money to keep ourselves going. I and my dad that time.

[The Caritas] was in a church, that is Catholic school because the person who was managing it was the Monsignor, which was the head of the Catholics there at Obowo. That’s where everybody would come to collect.

Sometime they had a sub station at Mbaise but that of Mbaise is filled up, but that of Obowu, where we have a relation who will always be considerate.

Monsignor Ogbonna. He is a reverend father. He’s a reverend father which he died and he heads the Catholic church so all this Caritas and the Red Cross food would always be coming to that place to be distributed to people who need them.

[The people I saw at that Caritas] some people lost weight. It was not just that normal, even when we go there, we also have fear that anything can happen. So immediately the relief is given to you, you start running down home. You start running down home.

But people were lively. But people were happy. We were happy believing that it would just end in a couple of months.

Really, what happened, I just opened up my eye to actually see that life is not a bed of roses. It’s more of an undefined clause.

Now that I have reached to this my stage, the only thing that can help is just to pray, just like in my church.

No, no, no, no, no. None of them [in my family died]. We came back and we had three boys and I was the first and the five girls. Some of them went back. All of us came back healthy.

All of them [cousins, uncles] were fine. All of them were fine.

When we came back, they were all happy that they have seen at least, it’s more of another family reunion.

Everyone is happy. Everyone was happy.