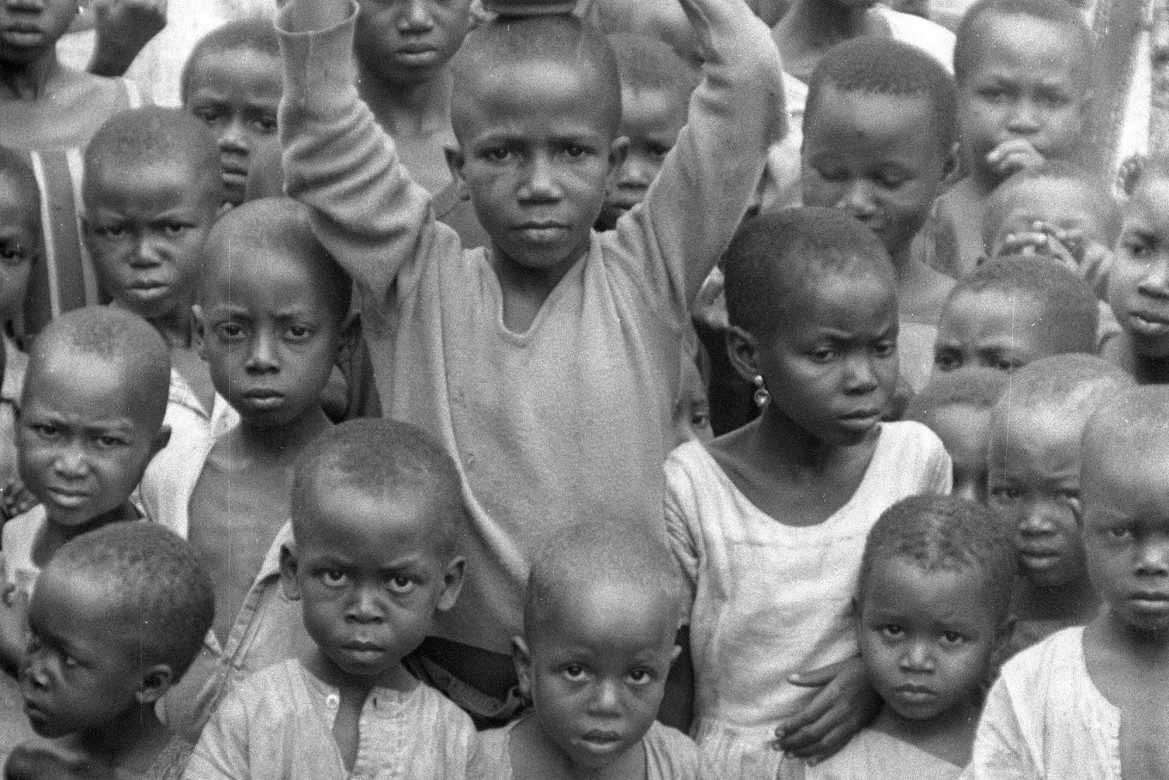

Medina Dauda remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah.

My name is Medina Dauda. I was born on the twenty fifth of October, 1958 in Kaduna, precisely in Unguwan Shanu of Kaduna north and I started my- would I say kindergarten? Because then we had the army children’s school that have this kindergarten. Creche was not much known then, because there were not much working class mothers so I started the kindergarten at the Army Children’s School, New Cantonment in Kaduna. That was in 1964. So by 1966, I was supposed to go straight into Primary 1 in Kaduna.

It was a terrible sight for a young child like me because it was January of 1966. I had just celebrated my seventh birthday by some few months then and then one morning, one early morning like that, normally I go out to ease myself alone without any company, but that morning, I wish I could remember the day. That morning, I wanted to go out and ease myself. First, I stepped out on my own and noticed that there was this brightness in the entire firmament covering everywhere at Unguwan Shanu.

So I was scared.

I went back in and told my mom she had to escort me out to ease myself and that is one thing I hardly do, really. So she was also taken aback when I insisted that she had to follow me outside. She did reluctantly and when we came out, she also saw that thing that drove me back in and was wondering what it was.

Actually, we were not too far from the rail line which was the dividing line between the village where I stayed and where the late Sardauna of Sokoto lives across to Unguwan Sarki area of Kaduna.

So the fire that engulfed the entire building was what brought about that brightness that we saw so we were all wondering, because none of us knew anything was going to happen. I would say I didn’t know. Maybe I didn’t know because I was a child, possibly there were talks about things that were going to happen around the more senior people, including my parents, but they may not let a child like me know since first possibly because they won’t to scare us, we have a lot of friends that we live together that are from the eastern part of this country. So you know, and then that just happened and I found it really, really strange and I was asking my mom, “What could this be? Why is the whole place changed and so bright like that, and it’s not morning yet?”

She also didn’t know, so she wouldn’t give me an answer. Well, we went back and slept until morning. When it was morning, the entire Kaduna town was in some kind of mess like that. People were running helter skelter. Some people who were supposed to have gone to work are not going to work. Some people who are supposed to have gone to the market are not going to the market. I noticed that strangeness and I was supposed to go to school that morning and my mom said ‘No. We’re not going to school today.’ I said “What for?”

I never saw him again

In the compound we were, we had some Igbo people who were living with us. I could remember this tall, lanky, fair skinned man who had his family. From that day on I didn’t see him, because I know that he leaves the house very, very early every day, either a working day or a weekend.

Medina Dauda. Photo by Chika Oduah

I wouldn’t know what he was doing for a living. Possibly he had shops somewhere or something but he was always out very early. Then, I remembered that from that morning, he could’ve left early, but I never saw him again, and all of those people who lived with us that were from the eastern part. I didn’t see anybody again. Now, what I noticed from that day, the little change that I noticed was that most of those familiar people from the East were not around again.

Possibly they hurried back to the East or something.

And then I noticed a lot of influx of young men and I asked my dad what are all these young people doing?

Every day I see them in shorts with white shirts in large groups of about 50 to 100 of them, doing some kind of exercise, so I asked my dad what all of this is about, and my dad said those ones are new recruits in the army. And I was like it wasn’t like that before.

You know the child’s mind and thinking. I could’ve been asking my dad all these questions and he would be like, ‘You are too inquisitive. This does not concern you as a child so you should not be asking,’ so I just said to my dad three days after, how come you people refused me going to school, and I noticed that most of the children in the area too, they’re at home. They were not going to school. My dad said no, that it’s not safe because the country is in a kind of trouble.

I said trouble?

He said yes. I said, ‘what’s the kind of trouble? He said war broke out because some soldiers killed most of the leaders that we have in the country. I said ah ah, why would soldiers do that? Are soldiers not part of the same part of the same government?’

That’s the inquisitiveness of a child. I was just asking my dad all of those questions, not knowing it was a really big thing that Nigeria was going into war.

Would I call it a grave?

Medina Dauda. Photo by Chika Oduah

Well, when a little bit of it subsided, we were asked to go out to school because it seems the fighting was not much in the upper part of the north, so my dad said to me one morning that you could go to school tomorrow Monday, but your mom must escort you, and my school is around the army barracks, that’s the New Cantonment, so she escorted me to school and we went and we met teachers and some pupils, so we were attending school.

But we were made to close much earlier than the normal closing hours and then again I noticed that those that were in a higher class than ours, like Primary 2, 3, 4 were being made to go out to dig some kind of shallow, what would I call it?

Would I call it a grave?

Something shallow that one could lie in. Yeah. A shallow grave that you could lie in. Then, we were too young, you know, but we noticed most of out seniors were digging that and building it to a certain level, then teachers would like say everybody should dig one, that is the senior class. For us, we close at 12, so we don’t stay in school till up to 3 or 4.

they were scared of creating some kind of apprehension in us as children

I also noticed that there were always some kind of aircraft flying and hovering around, you know. I wouldn’t say it’s only one, because it’s like in a whole day, in a whole day you’ll find aircraft flying and hovering around, so I remember that I asked one of my classmates what are these aircraft flying for?

Could they be dropping something from the sky that we said we should dig shallow graves and lie in it?’ and she said she doesn’t know as well. When we asked questions, our seniors wouldn’t tell us anything that they know because they were scared of creating some kind of apprehension in us as children. Then, again I remember seeing trains passing every day after school, after 12 o’clock in the afternoon, on our way coming home, I see a whole load of soldiers in the train. The train, you know for us children we used to count the coach, the coaches, you know, we’d count one, two, three. Sometimes we’d count up to 10 coaches and all of it was full of soldiers in their green uniform heading somewhere in one direction, and we never see them come back.

So we just assumed that soldiers are going out to work or something.

We didn’t know that it was a real war that they were going to fight, but I remember seeing that as a child in Kaduna. And then what else? Uh…

Far into 1966, like towards the end of the year, schools were closed, lectures were suspended for any school, so we were also exercising that fear and by the turn of 1967, we now found out that most of those that our classmates from the Eastern region did not come back to school, so maybe they followed their parents back to the east for fear of what is going to happen.

Maybe the whole country is going to be engulfed in the war. Well, we grew up as children for that ’66-67, to ’68-’69, to 1970- almost four years of the war before it was almost over. I knew a lot of schooling was interrupted, you know, that I know, and then eventually, my parents removed me from the army children’s school New Cantonment to one primary school that is just across the road from the village where I was born and it was a local education authority school owned by a government, not by the army anymore and I thought it was just for my own safety, because the village where I was born, to cross over to the New Cantonment, there was a stream that I normally cross every day to go to New Cantonment, but across the road is much easier for me, I wouldn’t need any escorts. So I thought it was just one of those days.

I now went back to LEA Unguwan Sarki and started Primary 3 in 1969.

I went back there and started Primary 3. Already I had gone into from ’66-’67, I had gone into Primary 1 before my parents now took me out of the Army Children’s school before my parents took me to the local government school. Well, that’s the little bit I could remember but I can’t remember seeing people being killed in Unguwan Shanu, even though we heard that somewhere across the rail line where we used to have a market and they used to have a bus stop where people come there to enter local vehicles to go to other places.

Medina Dauda’s hands. Photo by Chika Oduah

We learnt that fighting took place around the market area and the bus stop area and that some people were killed but you know, honestly, I never saw a dead body. I never saw anyone around our street being killed, so possibly when that happened, they were maybe evacuated before people like us could come there to see what was happening as children, and even then they won’t allow us to go up to that level. Parents won’t let their children to go out to see things happening like that because they might be affected.

I had some Igbo friends. Would I remember all their names, now? I remember that I had Christiana as my friend. I had Regina. I had Mary, who was my classmate, and there were some male friends too who were in the same school with us. I remember there was a Paul, and there was a Godwin, but you know, we lived close to each other. We followed the same route every day to school but we never got so acquainted with the boys. It’s those girls that were my friends that, you know, I just didn’t see again. And there was no contact. There was nothing like writing of letters, and there were, even if there were telephones, we didn’t have one, so I won’t say there were phones that we could make calls or anything, and truly, they left and never came back. I don’t know if they were still alive up to when my parents changed my school, but I never saw them again anyway, and their parents, too.

My dad was always buying newspapers. I remember there was one that I usually love reading. I try to read Hausa language, and it was in Hausa language, Gaskiya ta fi Kobo.

nobody would explain, so we were just watching it as children

So there are pictures in it that I see. I see pictures of soldiers, maybe holding guns or something, but most of the pictures then were in black and white, so you could just watch the pictures the way you see them, and of course there were television. There was always the news that my parents would watch and would allow us children to come and sit down and watch, and we would watch the news. We watched the news readers, the news presenters. We watched the head of state making broadcast or talking to Nigerians in army uniform. We see a lot of activities, you know, with army then.

There were signs that really something is happening around the country that has to do with shooting, dropping of bombs, and other things like that, but again, nobody would explain, so we were just watching it as children, as if it was just a kind of film we were watching, so after the news, my parents would say to us, “Go to bed because you have something to do in the morning. You have to retire early.”

So by 9, 9:30, we would go to sleep, not knowing exactly what was happening, but at least, as I told you, we sense it as children that something is amiss when every day we have aircraft flying over us, hovering around, you know for a very, very long period.

My dad was telling me [we had relatives who were soldiers in the war]. I think I have three or four close relatives who didn’t come back from the war front. Some came back injured.

Yes, I remember I had a lot of relatives, really. My dad talked to me about a lot of his brothers and sisters, I mean brothers only who went to war, leaving maybe their wives or their siblings, like sisters that were around my home state and I remember too that some of my close relatives, either related to my mom or to my dad that came back from fighting the war alive but some of them came back injured and we had to always go see them in the armed forces hospital which was not too really far from where we were living. My mom and I normally trekked to that place to see them in hospital. I remember one’s leg was amputated. I remember that the other one was shot in the arm and he had his hand in a sling, or was in hospital.

In the hospital, I saw a lot of wounded people but you know, again, I could just be passing through them in the ward, but we’d only go to where our only relative is, to greet them and possibly take some food to them sometimes. I saw four of them that are my relatives through my mom and dad. My mother’s younger brother was in the army- two of her younger brothers were in the army. There was Mboto Ngomban, is the second born after my mom, and then there was Dan Azumin Gomban, who is the younger one to Mboto. Both of them were in the army and they are her younger brothers- same mother, same father.

For my father, he told me they had a lot of nephews who went to the army. He is related to then head of state, but you know as young as I was, I didn’t know what their relationship was until much after the war, then I realized that the then head of state, General, who is now General Yakubu Gowon- then he was a colonel I think, lieutenant colonel or colonel in the army when he was the head of state. I didn’t know that there was this relationship between him and my dad. My dad and Yohanna Gowon, who is Yakubu Gowon’s father are cousins. My dad was born in Lur of Kanke local government of Plateau State, where Payu Hanon Gowon came from. You know, the senior one is the father of Yohanna and the younger one is the father of my father. That’s my grandfather. Well, that little bit I know until I grew up, not knowing actually what the relationship was. Maybe as a child I could have forgotten some few things, but I remember they are from the same village, the same town, the same household as brothers from Lur of Kanke local government of Plateau state.

My dad now said, sorry, my dad said to me that he had a lot of cousins, nephews, who took part in the civil war. He told me then that there were more than twenty and he said most of them didn’t come back. That’s how close he was with those other relatives of his because he was able to know them. He was mentioning their names and most of them didn’t come back.

So after I became an adult, I realized that this Nigerian Civil War that we had read about affected me as well, because it affected my father and my mother’s relatives, which means, by extension, it affected me as their child.

Knowing that all of those my dad mentioned are from the northern part of this country, so it means the Biafran War affected some people from the north as well. It did because if I remember, those army, young army people we see in train coaches traveling off the north towards the east, must be Northerners. Most of them, if not all of them, must be Northerners, but to go away like that, and most of them never come back, and my dad was also saying some twenty of his relatives, and God knows only how many other people from the North lost so much relatives during that war.

At least I remember my few female friends that we were very close. I was already even learning to speak Igbo.

we did so much of injustice to ourselves

What I knew of the North, most of it was what I learned after I grew up. The north was, when I was in the primary school, senior primary school 5 and 6- because I never went to Primary 7. I just did up to Primary 6 and then I started secondary school but then Primary 5 and 6 were termed as senior primary schools then. I was able to know that most of my friends that came from Bauchi, Sokoto, in the Nigerian Civil War. So the civil war didn’t just affect the eastern part of Nigeria. If there was anything we could talk about- hurting each other, then we would say, as Nigerians, we hurt ourselves by fighting that war and I have a reason to say that because from the little I learned, it affected everybody. It affected the Northerners, it affected the Southerners, it affected the Easterners, and we had only three regions then.

So what else would you say?

Everybody was affected.

And if we could do that to ourselves, we were the originators of the war ourselves, because those who did that coup that killed the prominent leaders of this country are also Nigerians.

Medina Dauda. Photo by Chika Oduah

They didn’t come from other countries. They were also Nigerians. Nigerian youth trained in Nigeria. And I was even taken most aback to find out that Chukwuma Nzeogwu Kaduna, whose name was quote and unquote “Kaduna” was an adopted son of the late Sardauna of Sokoto.

He brought him up. He trained him in the army and then he turned against him and killed him, so we did so much of injustice to ourselves. All those young people. All those young soldiers who started that coup that led to protesting or objecting to what Britain did during the Nigerian Civil War. Well, that little bit I was able to read, but the truth is I don’t think almost three and a half or so years of pain for no reason, you know.

Children dropped out of school for no reason. Schools were closed for no reason. People were just killed for no reason.

Why did we have to do that?

Some other people are contending with external aggression. Ours was an internal aggression that I am so bitter about. I honestly would say after the war, we had leaders who were talking about the three Rs, reconstruction, re-whatever, re-whatever. But were those three Rs really implemented or carried out to the letter?

Were there any reconstructions? Was there any rehabilitation? Were there any rejuvenation of people’s psyche? Healing of so much pain and hurt?

*This interview was conducted in Abuja, Nigeria