Dr. Emmanuel Oduah remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

My name is Dr. Emmanuel Oduah. I was born at Odekpe, Ogbaru Local Government, Anambra State.

December 24, 1954. December 26, 1954.

When the war broke out, I was at Onitsha in Anambra State. Well, it was eastern Nigeria, then. That was where I was. And the war broke out. When you say war, you talking about the crisis?

In 1967 I was at Onitsha, in Anambra State. We were in school. In 1967, when the war broke out, so we left. I went back when there was crisis. Everybody was running around. We were there until they destroyed the Niger bridge. When the, I think they were trying to cross over from Asaba, the Nigerian troops. And the Biafran soldiers broke the Niger bridge and that was when we moved back to the village, Odekpe, in Anambra State.

I was in elementary school, actually in high school. In Nigeria, that time. 1967. That’s where I was last.

It was a secondary school.

I did not join the army. During the war, I was in the village. My experience during the war wasn’t that horrible because we were in the village doing some farming, some fishing, and some trading, but I did see a lot of people as refugees come in from so many areas. At a point, when the war broke out in 1967, when Onitsha fell, so many people came staying in our house. At that point, we were up to a hundred people living there, staying there, for several months and it wasn’t a very horrible experience but we were just there, welcoming people who lost their home, who lost everything they had. But for me as a person, I was too young to join the military.

As a matter of fact, in 1967, I went to St. Charles Teaching College at Onitsha to join the military, but getting there -I went with a friend- on getting there, the major told us we were too young to join the army. That we could not fight. We should go back home. He said he was telling us because he came from our place and we could not join the military. We were too young. So we left and went back. Going back to the village, staying there, no school, and because we were farmers, we went into the River Niger to fish.

There was a huge market, that’s my home town, at Atani. There were markets everywhere. So we were selling fish, a lot of vegetables, and then we went to the woods to get so many fruits. It wasn’t quite bad for me. I wouldn’t say that I enjoyed the war but I didn’t suffer. Just like so many people did because we did not run from our home town.

One of the military boys- saw me and said “Come on.”

I wanted to join the Biafran military because I saw so many young guys, the way they dressed, the military boys. Some people joined the navy, some people joined the army, some people joined the Air Force. I just liked the way they dressed, and how they looked sharp, and they were carrying guns and walking around. People were respecting them. So I said I needed to join this, to be a part of it.

When things were good- the military boys were eating good, and everything was good. They denied me because I was young. Then, one day, when they started conscription, drafting in the, I think I was just coming out from the river area and somebody just- one of the military boys- saw me and said “Come on.”

He pointed a gun at me and I said “What is it?”

He said, “Join the line.”

I said what is it? Because they know me and the guy, I called him his name. I think his name was Ben. I said “What is it?” He said “Join the”- so I went over there and we marched forth to a Ogbe Etiti, small elementary school there, and they were going round the whole village conscripting young men to be taken to Atani.

I said what is it? and they said it’s conscription. On my own, I went over there to join the army, and they said I was too young.

Dr. Emmanuel Oduah’s hands. Photo by Chika Oduah

Now that things have gotten bad, they wanted to conscript me. I didn’t want to join, but then my elder brother, Uche, was in the army. He already got to the war front and got injured and he came back to the village, recuperating. So he came to the school where they put us and he said, “What are we?” He said that I was going to the army, but he said he would see what he could do so that I could escape. So one of the young men, Edwin, who was also a soldier, on the post guard, so my brother started talking to him, because Edwin was my cousin as well, so I said okay.

Edwin just looked up and we jumped the fence on that school and ran to the woods. Me and another guy. Two of us. They released about two or three shots.

Then, we were already in the woods, and there were lake in the woods where they were doing fishing. We just entered and swam in the lake and going way inside the bush. They were really not pursuing us, because even though, so I escaped. We stayed in the woods for hours and they took all those boys, a lot of them, to Atani. Put them in a truck and some of them joined the military and some of them did not, but that was the first conscription, so I escaped that.

Another time, about 1968, they came again. I had a friend who was at the headquarters 11th division. It was, they call him Bodyguard, to the Colonel who was in charge- one Colonel. They call him Ifeomata. So we were friends. I went to the school to visit them. While I was going back home, they said that the young men will work and clear the roads, clear the roads and they used the cutlass to cut the grass and things like that, but that was just to get people into conscription. So when young men came out, they gathered all of them and marched them.

Dr. Emmanuel Oduah’s hands. Photo by Chika Oduah

I was coming back home and I saw the line. I kept coming. I didn’t know where they were going, so one of the officers said join the line. I said for what? He said join the line. I did and we started walking all the way and they said this is conscription. I said no, I’m not going, but you can’t escape so we were walking all the way from Odekpe to Atani on foot. This long line. Any young man they saw, anywhere, they just said join the line, so getting to Atani, that time, by then, my mom was home, but there were some people who went to the market at that time, so they saw me. They were shouting and they were crying and they told my mom and my mom ran from home and came and my sister was, at that time, married, so my mom came straight to the big school- I think St. Joseph Secondary School- no, no, St. Joseph Elementary School, where everybody was.

I went to the bushes.

They lined us up and there was a captain that was looking at every body. My mom was there, my sister was there, and he was just standing there. And he looked at me. My mom said look, this is my son. He is too young to join the army. He can’t go. The captain, the officer looked at me. He said he’s young, he can’t carry the gun, so he said get out. Go with your mom.

While we were leaving, another sergeant said that man is not too young. My mom said no, no, no, no, no. They exchanged words. The officer said that my son is too young. You can’t say that he’s not too young. The boy said well he is younger than me because I was tall. I said well no. My mom was not happy with him. The officer came and said let that boy go. I was just lucky. We left and I went to my sister’s house at that time. We stayed there until we took those guys to Nnewi. One of them joined, so that was two times I escaped the conscription. So, answer to your question: During the war, I did not join the military.

I went to the bushes. There was a lake. We were swimming. When we went to the bush, then that was where the water. So we swam into the water.

I don’t know the name of the lake. It was in Odekpe. It was in all those man made lake that they go fishing at a point.

It’s not a big lake. We jumped in there from the school, jumped to the woods, jumped to this water, this lake, and swam across the lake so that they will not come to us. It wasn’t river.

That was the first conscription from the school.

I didn’t have blood relatives that were killed [in 1966] but I had some distant cousins, not really cousins, but acquaintances that were killed. For instance, the guy that was living in front of my house. He was butchered. They almost cut his ear and he was one of those that they thought that he was dead. Put him in the train and shipped them from Kano to Enugu, and another one, Sunday, who was related to my mom. Somehow, the same thing happened but they didn’t die fortunately. So I don’t have any close relative that was killed during the crisis.

They were coming to Enugu. I was in the village. I was too young [to go to the train station to see them.]

I didn’t see [the Niger Bridge fall], but when we heard the inci- dynamite that broke the bridge. So a lot of people were just rushing to see what happened and the military boys were chasing us that go back, go back, go back, but you know, there was huge- loud noise, and smoke were everywhere on the other side of the Niger Bridge, then we ran- cause I was at Fegge that time, Fegge, Onitsha. That’s where the Niger bridge crossed. Ran towards it but they were chasing us.

Fegge. That is where you go to cross the Niger Bridge at Asaba and it is in the same location now. So that is how I saw it. That’s how I- I didn’t go close to it.

Odekpe was the beginning of Ogbaru and Odekpe was not captured. Odekpe did not run. No town in Ogbaru ran because Odekpe did not. Some of them were saying we were just waiting for Odekpe to run, but the military, they kind of surrounded Odekpe because they came close to Idemili. Now, they were everywhere. So at a point, when we go out, we could see them [Nigerian soldiers] when we go fishing, but we did not run. Odekpe didn’t run, Atani didn’t run. Ota. Because they [Nigerian soldiers] didn’t cross over. They didn’t cross over. Coming from the other part of Nnewi, the other side, they stopped there. They didn’t cross into Atani.

Then, there was no other way they could come. There were at Ugwuta, so there was war at Ugwuta.

Why didn’t we run? Because they did not invade our town.

Yeah we were all together during the war, so we did not run because they did not- I mean, I don’t know exactly why, but crossing to the other side of the River Niger. They were there at Oko. We go fishing. Sometimes we come close, they shoot, just telling us they warning us and just run. There was a time what they called gunboats. It was floating from Atani, but those people came from the River Niger, through Warri area, from Warri to Onitsha. But we still did not run. They were shooting. I think sometime they would kind of bomb, but they wouldn’t touch our town. So because we were at the beginning from Onitsha, that was the point for Ogbaru. Odekpe was the first town, so people were saying, we were waiting for them to come. Some people thought that. I don’t know the reason why, but they didn’t invade Odekpe. We had some aircrafts and some air raids one or two times, you know. They would fly over.

The navy quartered at Atani. There was a gun boat. There was a military post along the River Niger. They had military post on the other side for the Nigerian troops. There was no serious combat, no serious confrontation. I think towards the end, say 1968-69, they became friends with each other, those in the battle field, because my brother who was there, they had little canoe and then this is a stream, Idemili River, very just narrow river.

So sometimes they would push that little canoe to the other side of the Nigerian soldiers. Those staying at Onitsha and they would put all these soap, some kind of drink like beer and all that and put it and say you hungry people just go and share all those things. So they were giving them something. One day I was over there because we were cooking and sending food to the military. They were cooking cow and so one day one guy shouted, why we dey kill ourselves where Gowon and Ojukwu dey stay somewhere and enjoy? Make we no dey kill ourselves.

So they became kind of tired of the war and became friends, so they were not trying to raid our town. So the borderline was that we did not run.

It was up to 100 refugees

When the war was over, it was announced that Biafra has surrendered. I had radio in my room, my brother’s room. So they said that Ojukwu left the country, that Biafra surrendered. The war was over. Everybody was already tired so there was so many jubilation when they heard that, both the Nigerian soldiers and the Biafran soldiers. People were running, so, this war is over, this is over.

So the Nigerian troops, that same day, just crossed. There was markets- at Eke market at Odekpe. They filled up the market and they were giving money out to so many people. It was celebration, that the war was over. Some people were shooting in the air, you know, the this war is finally over because a lot of people were dying of hunger and all that kind of stuff. So that’s all we heard about. We heard it on the radio.

It was up to 100 refugees [staying in our house]. Those related to my mom, to my dad, so many young men. I mean I didn’t feel it because these were all students. They were all in secondary school, you know. So they came and they had nowhere to stay. A lot of them live at Onitsha and Asaba. So they came and everybody was cooking. My mom, my sister. They were just cooking. And we were just eating, you know. Whatever they cook would be consumed immediately because there were so many people.

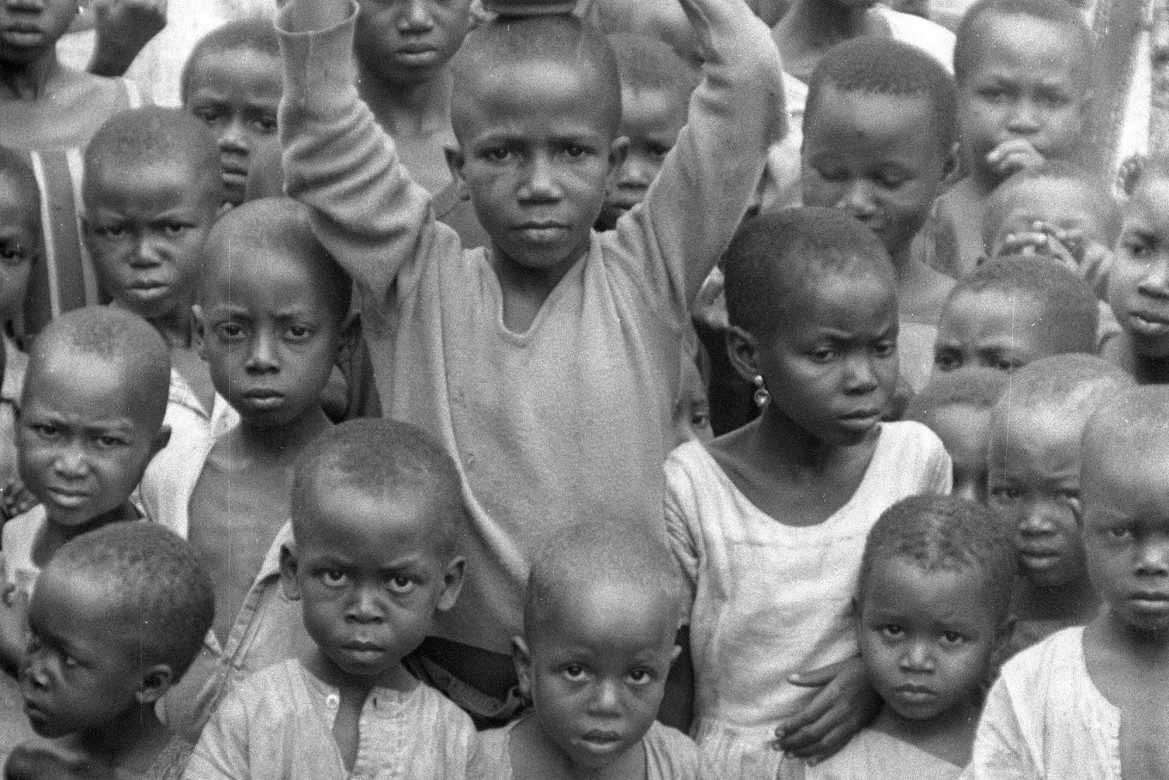

I saw it [kwashiorkor] Yes, I saw it. But not from my home town. People from other parts of the eastern Nigeria that time, yeah we saw kwashiorkor. Yeah some of them were coming to our side and they had a camp where they were feeding them because of all the- Our area became kind of the business center in terms of food. So we had yam everywhere. We had cassava, we had corn, we had vegetables. So whatever you were looking for, so a lot of people were coming. So people with kwashiorkor, they were bringing their children and they were eating. They were feeding them. Initially they were bringing something from Caritas International, World Council of Churches. They were bringing their cornmeal, stockfish, rice and all those to feed their people. They were doing that initially at a point but they stopped doing it. Probably because of transportation.

Dr. Emmanuel Oduah’s hands. Photo by Chika Oduah

Some people, when some of the soldiers crossed over they were saying they had the kind of ammunition they call mortar. They shoot it, you go like three miles or four miles. But they say when they wanted to shoot or aim it at Odekpe, it would be full of water. They wouldn’t see any land anymore, they wouldn’t see houses. So some people believed, we wanted to know what was protecting this town.

They said well, they had an idol they call Iyoji. That Iyoji was protecting the people, so when there was attack, when they try to launch attack, everywhere would be like water. I didn’t hear from the soldier, but they said that’s what the soldiers came to find out.

They just curiously came to find out what is protecting this town.

They said they would see [a wall of water]. Those that were aiming, of all those heavy machine guns that they were using mortar. They said they couldn’t see before. Before they would see houses, they will be aiming to shoot the houses then everywhere would be just like river. That’s what people say. I mean for me I didn’t hear that, but a lot of people, there was speculation. That’s what they said. Some of the Ogbaru people said well, Ogbekpe had something protecting them therefore, not only that they had the faith that there was something that is keeping them there. If the Odekpe people moved, then they would move.

I uh, the cause of the war, I may not know exactly, even though I was young, I was reading newspapers, I was listening to the radio, and we didn’t have TV at home that time but I think it was, it started during the crisis.

Yeah, what I knew then, what I heard, what I was reading from the newspaper then was it started from the crisis. When the military started killing the elected officials killed so many people from the north, northern Nigeria, carried by one Major Chukwuma Nzeogwu. From the north they killed Sardauna of Sokoto, they killed Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, and the finance minister that time, but the people that were supposed to carry out the operation from the east did not kill them. Of course Nnamdi Azikwe was not touched. Okpara was not touched. Francis was not touched, people like that. So from what they say, the Northerners became angry, saying that they killed most of their people but they were killing the Igbos on the street because that was the anger they were saying that they killed all the people, particularly the Sardauna of Sokoto but they did not kill Zik, they didn’t touch Ibiam and they didn’t touch all the Ibo people.

* This interview was conducted by Chika Oduah in Abuja, Nigeria