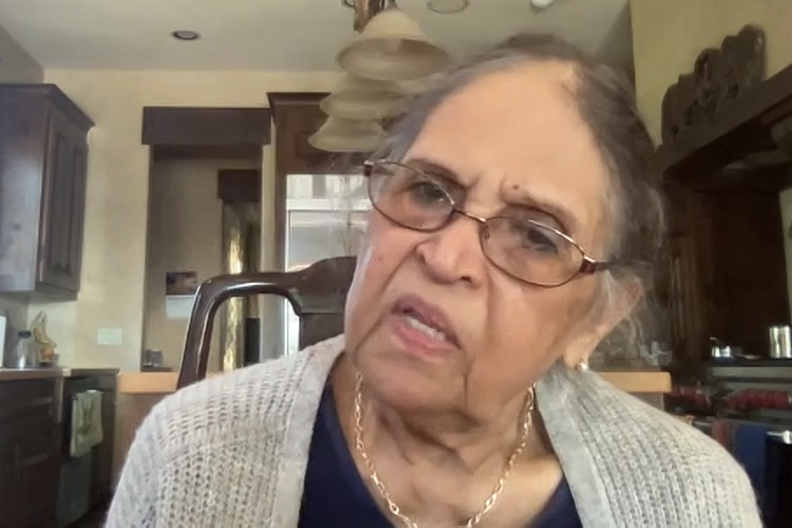

Prema Krishnan. I am from India, and my profession, a teacher. And I have two sons, seven grandchildren. I live in Houston, Texas. My husband also taught in schools, and he is no more. I was born in 1940, January the twenty-third. I come from the south of India, Chennai, and I speak Tamil.

I got married to Karur Krishnan, who had taught in Port Harcourt, Umuahia [sic]. He had finished his eighteen months contract in 1962. And then he came to India. We had known each other before he went to Nigeria and did his Masters. My husband comes from Trichy; that’s also in the south of India.

We got married and he came back to Port Harcourt in ’63 January, and he taught in Baptist College. I was still doing my Masters in India. So, I spent three months in Port Harcourt and I came back to finish my studies. And after that, he came to the end of his contract.

“Suddenly, we felt things were not safe.”

He liked traveling. So, he went to Ethiopia and came back in ’66. And I was expecting so I couldn’t go with him to Nigeria. He came back to India applying for a teaching Job, that’s when he got to Owerri. It was a beautiful town and I was pregnant as I told you so after having the baby in January ’66, I went to Owerri.

My husband taught biology, physics. It was a boys school. So, I joined him with my one-year-old baby, January ‘67. Everything was fine. We had travelled to go for shopping. We were happy on the campus. On the campus, there was one Indian family.

[Owerri reminded me of India] a little bit. I was homesick. I didn’t feel the same way in Port Harcourt. In Port Harcourt, there was so much to do. Clubs, markets, shops, more people, friends. So it was different from [the village where we were in].

And suddenly, we felt things were not that safe. We couldn’t get essential commodities. We used to go to the market to buy vegetables because we are strictly vegetarians. Things were not available, even in the store. And as I told you, we were in a remote place. And I remember when we drove to town, Owerri, some eighteen miles, we had to go on a bridge, which was a wooden log, no sides – eighteen miles to go shopping.

And one day, we were stopped while coming back to school. And they had guns. And he asked Krishnan, “Are you a Muslim?” And he said, “No we are Hindu. We are not Muslim. We teach in a school.” So, they let us go. We felt something was wrong. That was the beginning of the conflict between Mr. Ojukwu and Mr. Gowon. But we had no communication… no one would tell us what was happening.

Sugar, rice, vegetables were diminished. They were not to be found. And the other teacher who was on campus talked to my husband and we felt something was not right. And the school was closed. And then we came to know from others that there was a political problem. We were stuck. We couldn’t go for eight months. I was pregnant a second time.

We didn’t have a radio. We used to visit that family in Owerri city which was eighteen, twenty miles. And they heard, they told us, there was going to be a problem. But we didn’t have communication. Going out was not safe.

“That was the scariest, scariest feeling, that this could happen even where we lived.”

We were in a small village. I wish I knew more about that school now. If you find out please let me know. So, it was getting tough. No food, no communication, eight months. Our family didn’t hear from us.

When the war started, we were in a village outside of Owerri.

I’ll describe one incident. One day my husband, Krishnan, took the toddler child and went to Owerri to get some groceries. Up to one and a half hours, when he came, he and that toddler were covered in soil. Clothes were dirty. Hair was full of red soil. I said, “what happened?”

He told me, when he went to Owerri city and stopped in front of that store, anti-aircrafts were flying. And the store had trenches in front of it, so he grabbed the toddler and he laid in a trench and when it passed, it flew over him. That was the scariest, scariest feeling, that this can happen even where we live.

We stayed in Owerri, not the whole time but when it was intense and the anti-aircraft, that scared us. We had no communication. The Indian Embassy, we had no communication from our families. So my husband, the other teacher and there were two bachelor teachers in some other schools, they met and they decided we should flee because no one is going to help us to go and we cannot survive like this. So, they planned and they talked to some lorry person. He got a very simple boat that carries stuff that goes to Cameroon. So, one day early morning, four o’clock, we just packed a little millet for the toddler and one change of clothes. We left everything. We left our car. We left our belongings. But I carried pictures, because I didn’t want to leave them. Memories. I still have them.

So, at four o’clock in the morning, we left. We left our cars. We left everything. Just two pieces of clothes for the toddler and went to the gate. And the lorry took us and it was a four, five hours drive. I can’t remember. From the back of the Atlantic Ocean, the traders went to Cameroon. We went to the port and they said there was no room for us.

We couldn’t go back! So, we waited and we got into the boat. We were to sit in the same position. I was three months pregnant. The traders were operating the boat. They took the backwaters. The business people, the village people [were the ones operating the boats]. It was not a official.

“Eight months of worries, tension, fear.”

We came to Cameroon, Douala and spent one night in a hotel. Next, we went to Lagos because our former Minister of Education and other paper work so we went to the Indian High Commissioner who was very kind. He took us to his house. We stayed there for two days. You know, Barclays Bank in London? We used to keep our account [there]. So, we bought air tickets and within two days, we flew to India.

The Indian High Commissioner is supposed to help citizens. We asked, “why didn’t you announce that there was [a conflict]?” They said it was announced over the radio, but because we were out in a bush, the school was in a jungle, that small village, it didn’t have good service for radio.

[The conflict] was scary… It disturbs the normal lifestyle because you’re not sure. You’re in doubt what’s going to happen. It’s not only us. One local boy, his name was Sunday. And he would bring water for us from the creek, river, but we were afraid. We were afraid. We were not sure what was going to happen. But we were also worried about the local people.

“They said, they are going to the front to fight.”

It was scary; it was doubtful. What was going to happen? If the child falls sick, could we go to the hospital? Eight months of worries, tension, fear.

Our friends and relatives on both sides had no news from us. We left Nigeria in November 1967. It became intense after we left and things didn’t turn out peacefully.

That was the beginning. Students would play football and do exercises holding branches and carrying sticks. They were getting some kind of training and somebody told us, there is a problem. They said, they are going to the front to fight.

There were too many things happening. We wanted to go home safe. We were so so happy [in Nigeria]. The local people, they would speak broken English and we joke. But things changed. War is bad. Right?

We had a housegirl in our house named Comfort. She would come and babysit and play with the child. She came from a nearby village. But I don’t know what happened to her and all the other people when the war started. What was the biggest market? I forget the name. Very famous. Aba! We had gone there when we were in Port Harcourt. Sad. I always feel for the simple people in the villages. When I was pregnant with the second child, we left. We left in November and the baby was born in May the following year. Then we went to Zambia and we lived there until ’81.

I did not support either one of the leaders [Ojukwu or Gowon], because whatever geographical issues, states, you know, and religious issues, I could not judge. Each one was right in his own way. But I only wish that they could meet and talk, peacefully sort it out.

We had lived in a two-bedroom house. Living room, kitchen. On the campus, staff living on the campus of the school. The school was not a problem. Everything was fine. My husband enjoyed teaching in Umuahia, Port Harcourt, Owerri. The students were disciplined, very obedient, loving, hardworking. Teaching was not a problem.

I don’t remember the day Ojukwu declared Biafra because I was in my own fear and scared. So, I don’t remember. But there was no TV, no radio, nothing, no media. No newspaper. We could only hear hearsay.

I saw on TV later, much later [the conflict]. But we did see students using sticks, practicing and marching on the school playground. But we didn’t know what was happening. We didn’t know why they were doing it. Later we heard, they were getting practice to go to the front. Small students? That was sad. That was sad. I was scared. Anybody would be. War is bad.

Leave a Reply