Joy Onubogu remembers the Nigerian-Biafran War. Photo by Chika Oduah

I am Mrs. Joy Onubogu. I am from Ogidi in Anambra State. I was born in 1944. I am 73 years old. I live in Jos [in Plateau State, Nigeria] now.

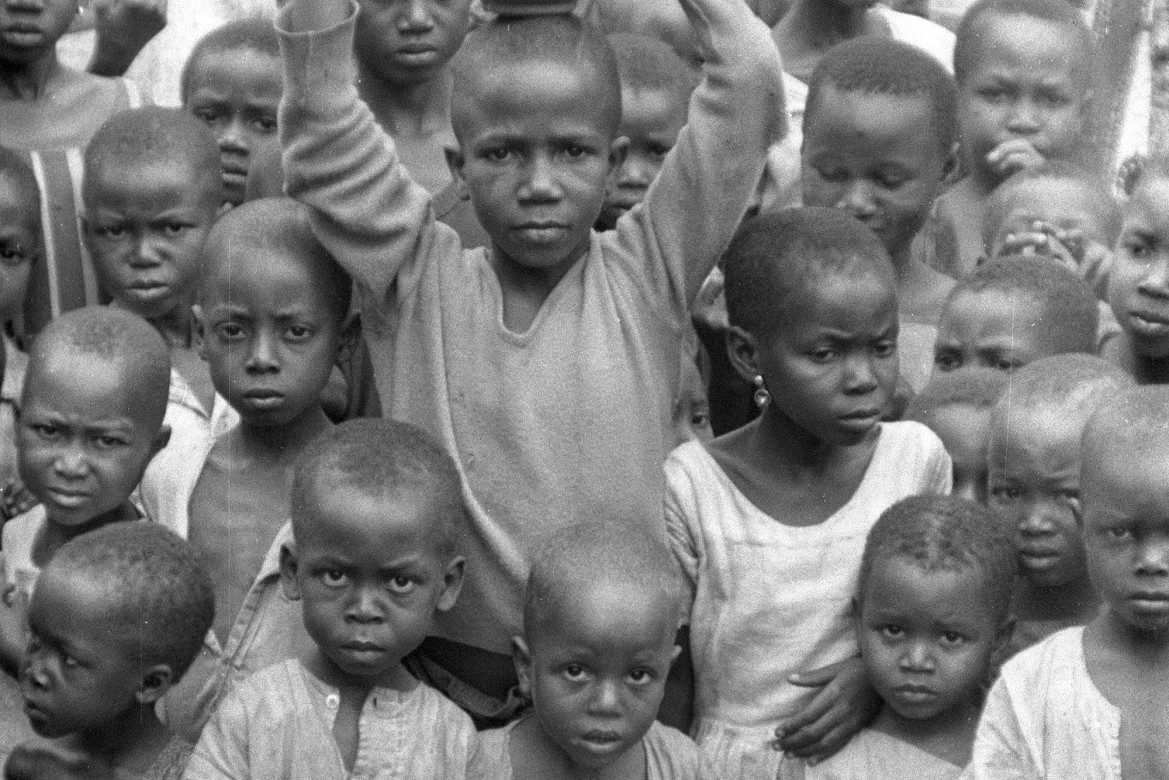

Each time Nigerian Biafran War is mentioned, the first thing that comes to my mind is the image of dead bodies, kwashiorkor children and suffering- extreme poverty and suffering.

During the war, the children, during the war, being a teacher, I remember the schools. We closed schools. Most of the children were worried [about] what would happen. We cannot run the schools when they were constant air raids. Rather, we had opportunity to teach the children how to lie flat on the ground each time they see the planes hovering over their houses. Before we knew it, food started getting more and more scarce. Up to a point that our people, you discover yourself that you have started sharing, struggling with some of the things we used to give to goats to eat. Children were losing weight until we can see your child and you see nothing but ribs. Kwashiorkor had invaded a lot of children. I can remember it clearly.

It is like every child carried a big head. I still remember one child that, even the parents left their children and ran because you cannot stand watching the plane hovering and we are still talking of children. Parents tried to get their children but it was a very pathetic sight to watch. And as I am giving this report, the memory is so sad. The memory of what we saw during the war.

When the war started I had finished my Teachers’ College and I was already teaching in St. Michael’s Boys’ School Aba. I was in Aba in 1967.

We started seeing dead bodies returning to Aba

Joy Onubogu. Photo by Chika Oduah

Many [of my] relations came from the North. They first started bringing back their children and the parents were worried. We sent messages to them to come back. The whole atmosphere was charged; you can see that there was a problem. Before we knew it, because my parents live near the railway line, we started seeing dead bodies returning to Aba. Many. Heads, some heads for us to identify. People were under – I don’t even want to think of what we saw.

They knew him and yet he was killed

I still remember one of my uncles living in Maiduguri, very wealthy. Everybody in my town believed in him. The whole community begged him to come back. He said no, that he is such a friend of Northerners. He has many hotels in Maiduguri. That nobody, nothing will happen to him, that he has empowered and enriched many of the Northerners, that they are his friends. That we shouldn’t worry about him. But since we are worried about the wife and children let them come back. And so they came back. But on one fateful day, we heard that he had been killed. Slaughtered, too. We couldn’t believe it. He was a friend to anybody that is important from the North. They knew him and yet he was killed. We lost many people in my village we lost many people. That is Chief George Nbonu.

Joy Onubogu. Photo by Chika Oduah

When the war started it was the sight of all these dead bodies that came back that actually forced people like me to join the militia, what we call Biafran militias. That is an opportunity to train everybody to know a little about war. We joined the militia and we were training. We do drills and we were given gun but it’s made of wood. We used all these things to defend ourself but there is nothing we can do to. It’s just to give us an idea of what carrying the gun means.

We would teach other people how to and what and what to do in case there is an air raid. The air raid, the planes come because the Nigerian army has not reached where we are but the fighting troops, mostly men or young young boys are the ones that fight. But ours is to help as a teacher to help children around.

At a point, when the war was getting closer to Aba, we had to run from Aba. But I knew my husband, he came with his car and picked all of us to his father’s station that is a bit far from Aba. That is Anara somewhere near Owerri. That is where we stayed and from there I got a job with the National Air Force Corps in Ntueke. Where we call Ntueke. And that is where I worked during the war with the former Vice President Alex Ekwueme. He was there, too, in that Ntueke.

He wasn’t sure he would survive the war so we felt there is no need to marry

I was 25, 26 years old [when the war started. Not yet [married]. The war delayed our marriage. We [my husband] met 1966. We were to marry ’67 but by that time he already lost two brothers in the war. I wasn’t sure he would survive. He wasn’t sure he would survive the war so we felt there is no need to marry. Very, very bad. We are not sure of surviving. He has already lost two brothers in one year.

Joy Onubogu. Photo by Chika Oduah

So we had to wait until, if the war ends and we survive it then we will marry.

Everything we had was taken away from us

So, by 1970 when the war ended, there was still another problem. No money to continue. Everything we had was taken away from us. And we were given only 20 pounds. So with that 20 pounds, we have to – things were even tougher after the war than even during the war. Because during the war we were sharing relief materials. People can get something to eat. But after the war, the Nigerian soldiers made it clear, told us clearly, in clear terms by the way they handled us that we were a defeated foe even though the government was announcing no victor, no vanquished.

…those who tried to look back were shot down

You see, we didn’t run with boxes because there is no way you can run away with a box. But some of the baskets, I can still remember the only surviving property I had was a set of spoons. And one day we were running – when the war ended, we were going to another – walking on foot to our village. We met the Nigerian soldiers and I think we came out with a vehicle too, a Volvo. They took the Volvo from us at that checkpoint where we met them, collected everything and asked us to look forward and be running. And those who tried to look back were shot down. In fact we were jumping over dead human beings so that we can survive. In that fear and fright, there is nothing we can do. We continued living like that until I met with the Nigerian Red Cross. I worked for the Red Cross [in Enugu] for a few months before there was calm in the community. We were sharing relief materials. Red Cross was sharing relief materials. We had an office; it is not a camp. People would come with their own complaints, what they have and what is happening. Then we attend to the need of the different areas. Some were coming from the nearby villages.

…we were jumping over dead human beings so that we can survive

Joy Onubogu. Photo by Chika Oduah

I cannot recount but many people died. I cannot count the number that died but they were many. Uncles, children, wives, old men and women. [But] my actual blood relations the same father and mother, nobody died. Because my father-in-law-to-be was a priest and he was sharing relief in the Caritas. Caritas were giving relief materials and he was sharing. So we had enough food to eat. So there was no problem with us.

We never lived in a camp. We lived within but most of our relations in many camps, we used to take food and relief materials to them. And if they know any day we are sharing relief in the area where we are; some of those whose camps were near will move to the place and collect corn flour or corn meal, stockfish, milk, and Ajinomoto. It is during the war that I saw that Ajinomoto first. I don’t know about it. I think it is a type of spice.

I have seen dead bodies being brought back for us in Biafra. I saw it clearly and being a teacher, what I understood is that the Northerners don’t want we people from the East anymore. So we have to – we came back and they pursued us to our place to kill us.

I will put him in the middle of plantain trees

The conscription; I have one brother and he is the only surviving brother of my parents. And he was 13, 14 years then. He was from King’s College; very brilliant boy. We were so worried, supposing they conscript him and he dies. So one of the things we do every night; I will put him in the middle of plantain trees. He will go and stand like a tree because the soldiers would come and search your rooms and search everywhere to see whether there were boys. If there are boys, they will conscript them. So I don’t normally sleep until I was able to arrange with some Biafran officers and they took him and put him in the camp and he started washing plates for some years. Because he was still very small. So when they come to search our homes and they won’t see any boy and they will go. But he will stand in the midst of the trees until early hours in the morning. By then we must have given him something to eat and then we will stay in the house just waiting. Many people lost their little little children. That is one of the reasons why the issue of Biafra is very dear to my heart.

Many people lost their little little children

[The] separation [was the most terrible part of the war], separating parents from their children many times.

Joy Onubogu’s hands. Photo by Chika Oduah

In fact, we came back with one child; one girl. The parents don’t know about her until after the war then they saw that the child is still alive. She has lived with us, that’s when they took the child. That separation was much. I believed that many people in Gabon today are Biafrans because a lot of Biafran children were taken over there. They have no parents to help them. Some of our teachers, too, went to Gabon. They teach children. But I had gotten a job with the National Air Force Corps so I couldn’t go to Gabon to be with them.

So that separation, when I remember it and when I see as people talk about Gabon. I said that, just the other day, I said to my husband that most of the people there answering Gabon may be our children that went there and settled there and since there are no mothers, no fathers they don’t know where they came from so they are now answering that they are from Gabon but while they are really, they are Biafrans.

The Igbos are not exaggerating the war. There was a lot of massacre. In fact, in filling stations, there were Nigerian planes that come and just pour bomb. In filling stations, it was as bad as that. You will all of a sudden, you will see nothing but dead bodies all over, people that were waiting to take fuel. I don’t think we are exaggerating.

It was a sheer waste of human lives

At least if you look at the pictures all around on Biafran children on kwashiorkor then you will know that actually we suffered. We suffered. We suffered. There is no exaggeration. In fact, I don’t think there is a word to explain the extent of which took place in Biafra or what the Nigerians did to human lives there. It was a sheer waste of human lives.

I am not here to judge whether it’s just – whether he [Chukwuemeka Ojukwu] served – you see I wasn’t there with him. I am not a military person. So, I don’t know.

Do you know that women, pregnant women were sliced open and dead babies?

Joy Onubogu. Photo by Chika Oduah

You cannot be in Biafra and not be a Biafran [at that time]. There is no way you cannot be Biafran. There is no way a group of people can bring back your dead bodies. Do you know that women, pregnant women were sliced open and dead babies? Babies were brought to the railway station as I told you. [I saw that ] with my two naked eyes. We lived close to railway station, that dead bodies – you go to check whether you will see anybody you know to carry. Some heads came back – it’s not – . Have you ever seen that book they call Pogram?

There is one in my parents’ room in those days. I don’t know if I am able to – it’s not exaggeration, it is reality. It’s real.

That is why we are saying that there shouldn’t be another war. Right now when I consider what is happening in Nigeria, I say to myself there shouldn’t be another war. Whatever we are doing should be done peacefully because the war does not favor anybody.

*This interview was conducted in Jos, Plateau State